[Martin] is working on a RFM69-to-MQTT bridge device. If you’re at all interested in DIY home automation, this is going to be worth following. Why? When your home automation network gets big enough, you’re going to have to think seriously about how the different parts talk to each other. There are a number of ways to handle this messaging problem, but MQTT is certainly a contender.

MQTT is a “lightweight” publish-subscribe framework that’s aimed at machine-to-machine data sharing, and runs on top of a normal TCP/IP network. IBM has been a mover behind MQTT since the beginning, and now Amazon is using it too.

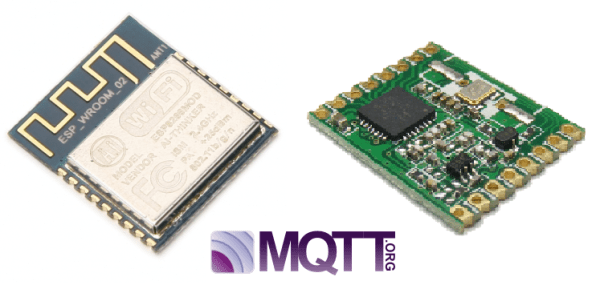

But most MQTT servers need a TCP/IP network, which pretty much means WiFi, and this can be a killer for remote sensors that you’d like to run on battery power, or with limited processing power. For these use cases, a low-power, simple sub-gigahertz radio module is a better choice than WiFi. But then how to do you get your low-power radios to speak to your MQTT devices?

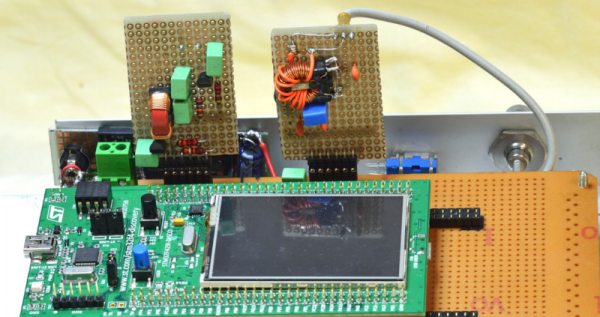

That’s the point of [Martin]’s MQTT bridge. Previously he had built a sub-gig radio add-on for a Raspberry Pi, and let the Pi handle the networking. But it looks like there’s enough processing power in a lowly ESP8266 to handle the MQTT side of things (over WiFi, naturally). Which means that you could now connect your 868 MHz radio devices to MQTT for less than the cost of two pumpkin spice, double-pump lattes.

On the firmware side, [Martin] has enlisted the help of [Felix], who developed the Arduino-plus-RFM69 project, the Moteino. [Felix] has apparently ported his RFM69 library to the ESP8266. We’re dying to see this working.

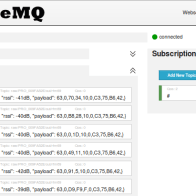

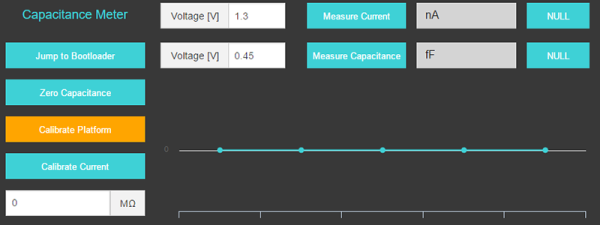

For now, we’ve got some suggestive screenshots which hint at some LAN-exposed configuration screens. We’re especially interested in the RFM + MQTT debug console window, which should really help in figuring out what’s gone wrong in a system that spans two radio protocols.

The bottom line of all of this? Super-cheap, power-efficient RFM69-based radio nodes can talk with your sophisticated MQTT network. Keep your eyes on this project.