Typical speed camera traps have built-in OCR software that is used to recognize license plates. A clever hacker decided to see if he could defeat the system by using SQL Injection…

The basic premise of this hack is that the hacker has created a simple SQL statement which will hopefully cause the database to delete any record of his license plate. Or so he (she?) hopes. Talk about getting off scot-free!

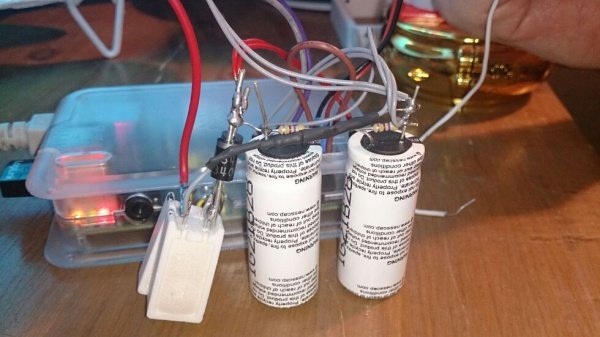

The reason this works (or could work?) is because while you would think a traffic camera is only taught to recognize the license plate characters, the developers of the third-party image recognition software simply digitize the entire thing — recognizing any and all of the characters present. While it’s certainly clever, we’re pretty sure you’ll still get pulled over and questioned — but at least it’s not as extreme as building a flashbulb array to blind traffic cameras…

What do you guys think? Did it work? This image has been floating around the net for a few years now — if anyone knows the original story let us know!