Compared to the human brain, a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) brain is positively miniscule, not only in sheer volume, but also with a mere 140,000 or so neurons and 50 million synapses. Despite this relative simplicity, figuring out how the brain of such a tiny fly works is still an ongoing process. Recently a big leap forward was made thanks to crowdsourced research, resulting in the FlyWire connectome map. Starting with high-resolution electron microscope data, the connections between the individual neurons (the connectome) was painstakingly pieced together, also using computer algorithms, but with validation by a large group of human volunteers using a game-like platform called EyeWire to perform said validation.

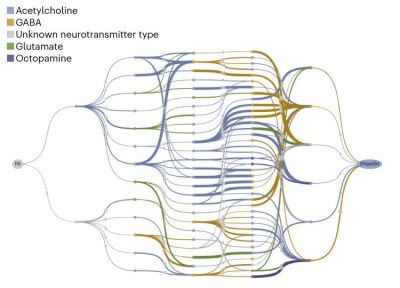

This work also includes identifying cell types, with over 8,000 different cell types identified. Within the full connectome subcircuits were identified, as part of an effort to create an ‘effectome’, i.e. a functional model of the physical circuits. With the finished adult female fruit fly connectome in hand, groups of researchers can now use it to make predictions and put these circuits alongside experimental contexts to connect activity in specific parts of the connectome to specific behavior of these flies.

Perhaps most interesting is how creating a game-like environment made the tedious work of reverse-engineering the brain wiring into something that the average person could help with, drastically cutting back the time required to create this connectome. Perhaps that crowdsourced research can also help with the ongoing process to map the human brain, even if that ups the scale of the dataset by many factors. Until we learn more, at this point even comprehending a fruit fly’s brain may conceivably give us many hints which could speed up understanding the human brain.

Featured image: “Drosophila Melanogaster Proboscis” by [Sanjay Acharya]