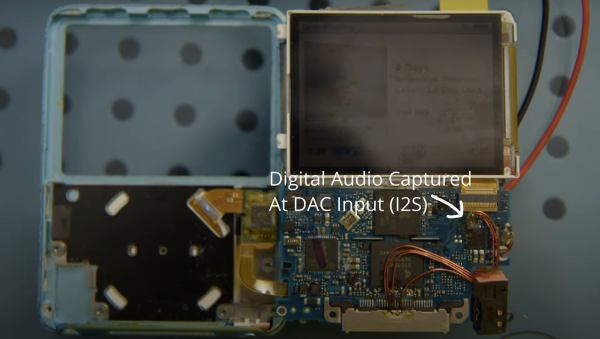

The iPod Nano was one of Apple’s masterworks, but it’s really tied down by its dependence on wired headphones. At least, that’s what [Tucker Osman] must have thought, as he spent an unreasonable amount of time designing a Bluetooth mod for the 3rd gen Nano. And it’s a thing of beauty — temperamental, brutally difficult to build, and fragile in use, but still beautiful. And while some purists try to keep their signal analog, [Tucker]’s coup d’etat is to intercept the iPod’s audio signal before the DAC chip, keeping the entire signal path digital to the Bluetooth speaker. Oh, and he also managed to make the volume and track skip buttons work, back across the wireless void.

Build Your Own 3D Printed Bluetooth Headphones

A few years back, [Shannon Ley] wondered how hard it would be to build a pair of Bluetooth headphones from scratch. Today, we have our answer. The Homebrew Headphones website is devoted to just one thing: explaining how you can use common components and some 3D printed parts to build an impressively comprehensive pair of wireless headphones for around $50 USD.

The headphones pair a CSR8645 Bluetooth audio receiver with a TP4056 USB-C charging module, a 500 mAh LiPo pouch battery, a pair of Dayton Audio CE38MB-32 drivers, and replacement ear covers designed for the Bose QuietComfort QC15. Some perfboard, a couple buttons, a resistor, and an LED round out the parts list.

The headphones pair a CSR8645 Bluetooth audio receiver with a TP4056 USB-C charging module, a 500 mAh LiPo pouch battery, a pair of Dayton Audio CE38MB-32 drivers, and replacement ear covers designed for the Bose QuietComfort QC15. Some perfboard, a couple buttons, a resistor, and an LED round out the parts list.

All of the components fit nicely into the meticulously designed 3D printed frame, and assembly is made as simple as possible thanks to an excellent step-by-step guide. It’s all so well documented that anyone with even basic soldering experience should be able to piece it together without too much fuss.

Of course, these aren’t the first 3D printed headphones we’ve ever seen. But the quality of the documentation and attention to detail really make these stand out.

Headphone Cable Trouble Inspires Bluetooth Conversion

[adblu] encountered the ever-present headphone problem with their Sennheiser Urbanite headphones – the cable broke. These headphones are decent, and despite the cable troubles, worth giving a new life to. Cable replacement is always an option, but [adblu] decided to see – what would it take to make these headphones wireless? And while they’re at it, just how much battery life could they get?

Armed with a CSR8635 Bluetooth audio receiver breakout module and a TP4056 charger, [adblu] went on rewiring the headphone internals. The CSR8635 already has a speaker amplifier inside, so connecting the headphones’ speakers didn’t require much effort – apart from general soldering difficulties, as [adblu]’s soldering iron was too large for the small pads on the BT module. They also found a 2400mAh battery, and fit it inside the headphone body after generous amounts of dremel work.

The result didn’t disappoint – not only does everything fit inside the headphone body, the headphones also provided 165 hours of music playback at varying volume. Electronics-wise, it really is that easy to retrofit your headphones with Bluetooth, but you can always go the extra mile and design an intricate set of custom PCBs! If firmware hacks are more to your liking, you can use a CSR8645 module for your build and then mod its firmware.

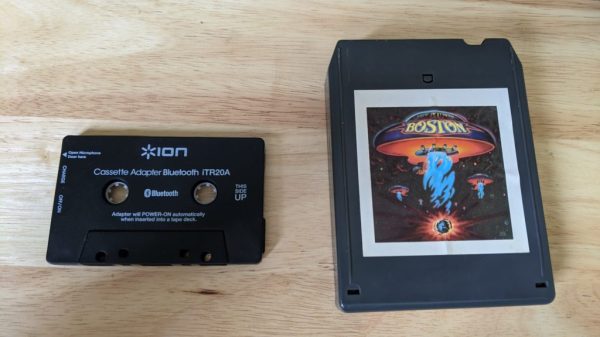

Bluetooth 8-Track Adapters Are A Thing

When it comes to classic cars, the entertainment options can be limited. You’re often stuck with an old cassette deck and AM/FM radio, or you can swap it out for some hideous flashy modern head unit. [Jim] had a working 8-track deck in his Corvette, and didn’t want to swap it out. Thus, he set about building himself a simple Bluetooth to 8-track adapter.

The hack is straightforward, with [Jim] grabbing a Bluetooth-to-cassette adapter off the shelf. These simply take in audio over Bluetooth, and pipe the analog audio out to a magnetic head, which is largely similar to the head that reads the cassette. Pumping the audio to the magnetic coils in the adapter’s head creates a changing magnetic field essentially the same as the audio tape moving past the cassette reader head. It doesn’t really matter whether you’re working with an 8-track player or a regular cassette. Get the magnetic field in the right spot, and it’ll work.

The electronics from the cassette adapter are simply placed inside an old 8-track tape, with holes cut in the chassis for the charge port and on switch. Then, all you need to do is pop the adapter into the 8-track deck, pair with it over Bluetooth, and you can get the tunes pumping.

Others have had success with hilarious Rube Goldberg methods, too. [Techmoan] took a classic cassette-to-8-track adapter, which is actually self-powered by the deck, and simply popped a Bluetooth cassette inside. That worked surprisingly well, and it was interesting to see how it all worked on the inside. We even saw a 3D-printed device on TikTok.

Thus, if you’ve got an old Corvette, particularly of that era with the Doug Nash 4+3 transmission, this might just be the hack for you. Alternatively, you can hack Bluetooth in to just about any classic stereo; we’ve got a guide on how to do just that. Video after the break.

Bluetooth Speaker Domesticated Through Firmware Mod

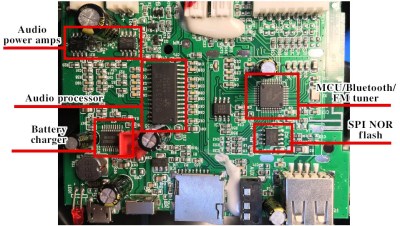

This might sound like a familiar problem – you get a Bluetooth speaker, and it sounds nice, but it also emits all kinds of weird sounds every now and then. [Oleg Kutkov] got himself a Sven PS460 speaker with FM radio functionality, but didn’t like that the “power on” sound was persistently loud with no respect for the volume setting, and the low battery notification sounds were bothersome. So, he disassembled the speaker, located a flash chip next to the processor, and started hacking.

Using a TL866 and

Using a TL866 and minipro software, he dumped the firmware, and started probing it with binwalk. The default set of options didn’t show anything interesting, but he decided to look for sound file signatures specifically, and successfully found a collection of MP3 files! Proper extraction of these was a bit tricky, but he figured out how to get them out, and loaded the entire assortment into Audacity.

From there, he decided to merely make the annoying sounds quieter – negating the “no respect for the volume setting” aspect somewhat. After he exported the sound pack out of Audacity, the file became noticeably smaller, so he zero-padded it, and finally inserted it back into the firmware. Testing revealed that it worked just as intended! As a bonus, he replaced the “battery low” indicator sound with something that most of us would appreciate. Check out the demo video at the end of his write-up.

Domesticating your Bluetooth speakers tends to be called for. If you can’t do that for whatever reason, you can rebuild them into an audio receiver – or perhaps, build your own Bluetooth speakers, with aesthetics included and annoyance omitted from the start.

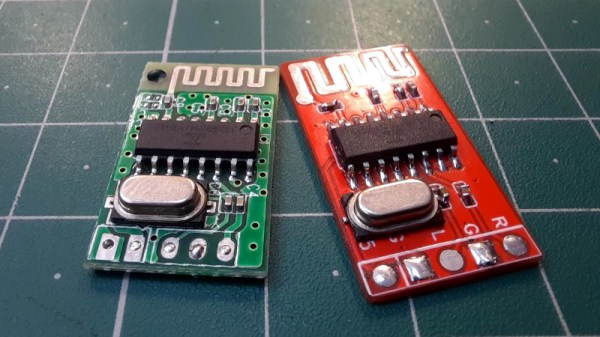

Reverse Engineering Your Own Bluetooth Audio Module

There was a time when we would start our electronic projects with integrated circuits and other components, mounted on stripboard, or maybe on a custom PCB. This is still the case for many devices, but it has become increasingly common for an inexpensive ready-built module to be treated as a component where once it would have been a project in its own right. We’re pleased then to see the work of [ElectroBoy], who has combined something of both approaches by reverse engineering the pinout of a Chinese Bluetooth audio chip with minimal datasheet, and making his own take on an off-the-shelf Bluetooth audio module.

The JL_AC6939B comes in an SOIC16 package and requires a minimum number of components. The PCB is therefore a relatively simple proposition and indeed he’s fitted all parts and traces on one side with the other being a copper ground plane. It’s dangerous to assume that’s all there is to a board like this one though, because many an engineer has come unstuck trying to design a PCB antenna. We’d hazard a guess that the antenna here is simply a wavy PCB line rather than an antenna with a known impedance and bandwidth, at the very least it looks to have much thicker traces than the one it’s copying.

It’s possible that it’s not really worth the effort of making a module that can be bought for relative pennies ready-made, but to dismiss it is to miss the point. We make things because we can, and not merely because we should.

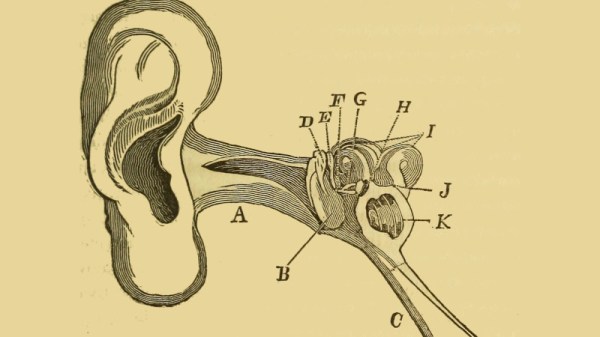

Surgically Implanted Bluetooth Devices Don’t Help Would-Be Exam Cheats

A pair of would-be exam cheats were caught red-handed at the Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Medical College in Indore, India, as they tried to use Bluetooth devices surgically implanted in their ears for a bit of unauthorised exam-time help.

It’s a news story that’s flashed around the world and like most readers we’re somewhat fascinated by the lengths to which they seem to have been prepared to go, but it’s left us with a few unanswered questions. The news reports all have no information about the devices used, and beyond the sensationalism of the story we’re left wondering what the practicalities might be.

Implanting anything is a risky and painful business, and while we’ve seen Bluetooth headphones and headsets of all shapes and sizes it’s hardly as though they’re readily available in a medically safe and sterile product. Either there’s a substantial rat to be smelled, or the device in question differs slightly from what the headlines would lead us to expect.

Continue reading “Surgically Implanted Bluetooth Devices Don’t Help Would-Be Exam Cheats”