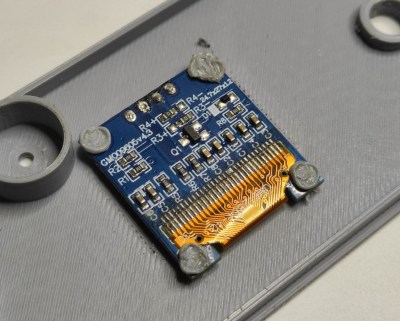

For our next installment, I have a lovely and daring PCB submitted by one of our readers, [Vas]. This is an ESP32-S3 board that also has an onboard round TFT display, very similar to the one we used on the Vectorscope badge. The badge is self-sufficient – it has an ESP32, it has a display, a programming connector, two different QWIIC ports you could surely use as GPIOs – what’s not to love?

This is a two-layer board, and I have to admit that I seriously enjoy such designs. Managing to put a whole lot of things into two layers is quite cool in my book, and I have great fun doing so whenever I get the opportunity. There’s nothing wrong with taking up more layers than needed – in fact, if you’re concerned about emitted/received noise or you have high-speed interfaces, four-layer is the way to go. But making complex boards with two layers is a nice challenge, and, it does tend to make these boards cheaper to manufacture as a very nice bonus.

Let’s improve upon it, and support [Vas]’s design. From what I can see looking at this board, we can help [Vas] a lot with ease of assembly, perhaps even help save a hefty amount of money if they go for third-party PCBA instead of sitting down with a stencil – which you could do with this board pretty easily, since all of the components on it, save for the display, are the ones you’d expect JLCPCB to stock.

Continue reading “PCB Design Review: ESP32-S3 Round LCD Board”