[Machining and Microwaves] has long wanted to use a 3D printer to print RF components for antennas and microwave lenses. He heard that Rogers — the company known for making PCB substrates, among other things — had a dielectric resin available and asked them if he could try some. They agreed, with some stipulations, including that he had to visit their facility and show his designs in a video. Because of that, the video seems a little bit like a commercial, but we think he is genuinely excited about the possibility of the resin.

Since he was in their facility, he was able to interview several of the people behind the resin, and they had some interesting observations about keeping resin consistent during printing and how the moonbounce feed he wanted to print would work.

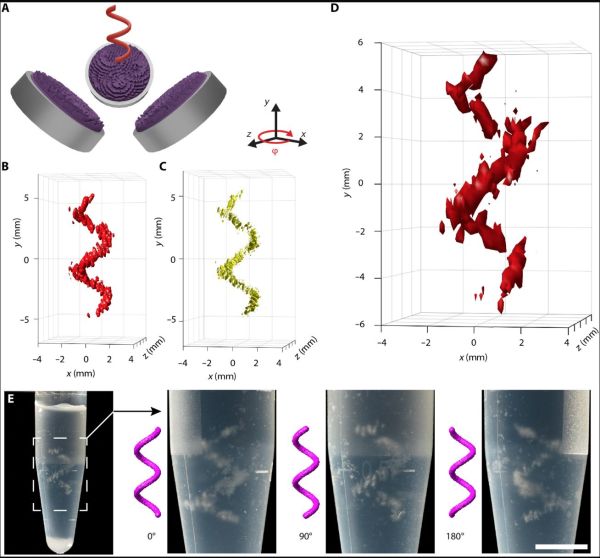

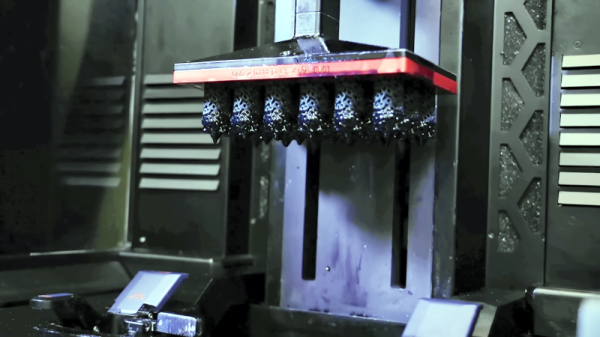

Some of the exotic RF test equipment was interesting to see, too. The microwave lenses look like some kind of modern art. According to the Roger’s website:

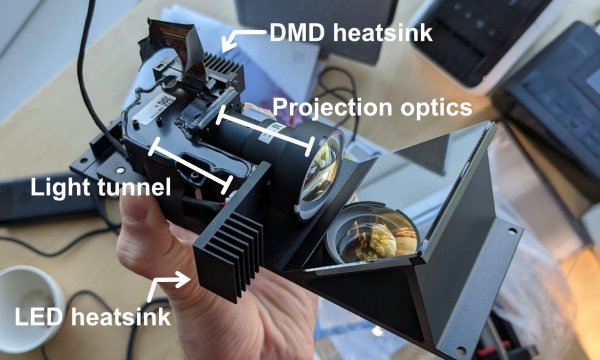

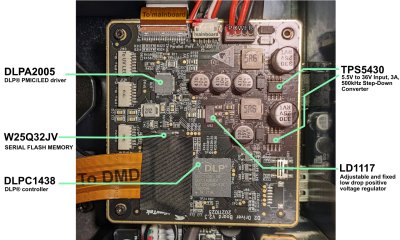

Radix Printable Dielectric materials are a ceramic-filled, UV-curable polymer designed for use with photopolymer 3D-printing processes like sterolithography (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP) printing. These materials and printing processes enable the use of high-resolution, scalable 3D-printing for complex RF dielectric components such as gradient index (GRIN) lenses or three-dimensional circuits. The 2.8Dk printable dielectric is designed to have low loss characteristics through millimeter wave (mmWave) frequencies and low moisture absorption for end-use applications.

It isn’t clear to us that you could use this resin in your own printers, but they did look pretty similar to what we have hanging around except, perhaps, for the continuous circulation of the resin pool. We figured the resin wasn’t inexpensive. In fact, we found a liter online for $1,863. We don’t know if that’s the suggested retail price or not, but we also suppose if you need this material, you won’t be that surprised at the cost.

If you don’t need microwave frequencies, you might be able to get by with some easier techniques. Or, you can even do something slightly more difficult but probably a lot cheaper.

Continue reading “3D Printing Antennas With Dielectric Resin” →