As the common myth goes, the average human utilizes only about 10% of the true potential their smartphone is capable of. Especially when it comes to electronics projects, it seems that we often overlook how we can integrate and take advantage of their functionality here. Maybe that’s not a big surprise though — while it isn’t rocket science, getting into mobile development certainly has its hurdles and requires a bit of commitment. [Victor Diaz] figured there had to be a better way, so he went on and created PHONK, the self-contained creative scripting toolbox for Android.

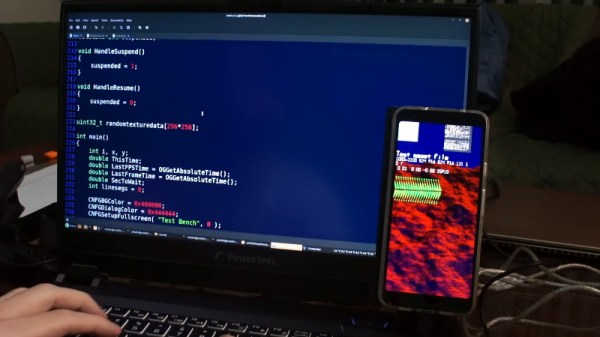

PHONK is installed like any other app, and allows rapid prototyping on your Android device via JavaScript by abstracting away and simplifying the heavily boilerplated, native Java parts. So instead of setting up an app from scratch with all the resources defining, UI design, activity and application lifecycle management — not to mention the Android development environment itself — PHONK takes care of all that behind the curtain and significantly reduces the amount of code required to achieve the task you’re actually interested in. In case you’re worrying now that you have to actually program on your phone, well, you can, which can definitely come in handy, but you don’t have to.

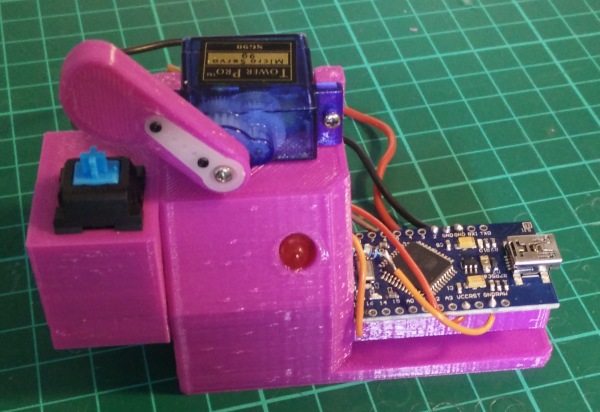

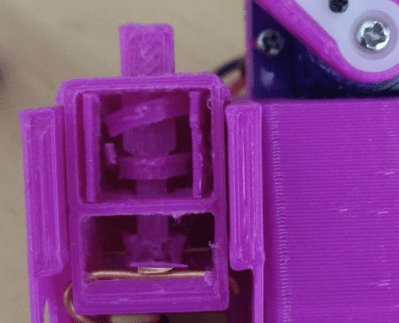

Once the app is opened, a web server is started, and connecting to it from any modern browser within the same WiFi network presents you the PHONK development environment with everything you need: editor, file browser, console, and API documentation. You can write your code in the browser, and pressing the run button will execute it straight on the device then. As everything is self-contained within the app itself, no additional software is required, and you can start right away by exploring the set of provided examples that showcase everything supported so far: sensor interaction, BLE server and client, communication protocols like MQTT or WebSockets, OpenStreetMap maps, and even integration with Pure Data and Processing. Attach a USB OTG cable and you can program your Arduino, have serial communication, or interface a IOIO board. You can even connect a MIDI controller.

This is really impressive work done by [Victor], and a lot of attention to detail went into the development. If you have an old Android phone collecting dust somewhere, this would be a great opportunity to revive it and build something with it. And as [Victor] writes on the project’s GitHub page, he’s always curious what people will come up with. If you’re thinking about building a mobile sensor lab, or want to learn more about the sensors inside your phone, have a look at the 36C3 talk about phyphox.