It has become a common sight, a must-have feature on modern cars, a row of ultrasonic sensors embedded in the rear bumper. They are part of a parking sensor, an aid to drivers for whom depth perception is something of a lottery.

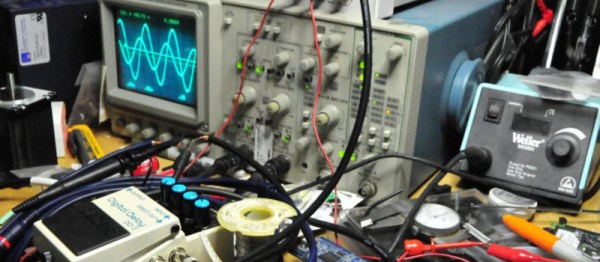

[Haris Andrianakis] replaced the sensor system on hs car, and was intrigued enough by the one he removed to reverse engineer it and probe its workings. He found a surprisingly straightforward set of components, an Atmel processor with a selection of CMOS logic chips and an op-amp. The piezoelectric sensors double as both speaker and microphone, with a CMOS analogue switch alternating between passing a burst of ultrasound and then receiving a response. There is a watchdog circuit that is sent a tone by the processor, and triggers a reset in the event that the processor crashes and the tone stops. Unfortunately he doesn’t delve into the receiver front-end circuitry, but we can see from the pictures that it involves an LC filter with a set of variable inductors.

If you have ever been intrigued by these systems, this write-up makes for an interesting read. If you’d like more ultrasonic radar goodness, have a look at this sweeping display project, or this ultrasonic virtual touch screen.

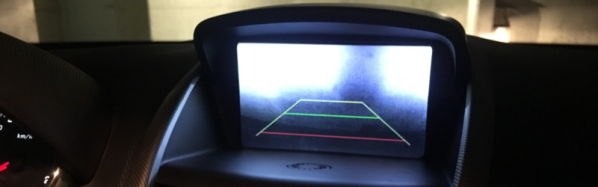

Adding the camera was the easiest part of the exercise when he found an after-market version specifically meant for his 207 model. The original non-graphical display had to make room for a new HDMI display and a fresh bezel, which cost him much more than the display. Besides displaying the camera image when reversing, the new display also needed to show all of the other entertainment system information. This couldn’t be obtained from the OBD-II port but the CAN bus looked promising, although he couldn’t find any details for his model initially. But with over 2.5 million of the 207’s on the road, it wasn’t long before [Alexandre] hit jackpot in a French University student project who used a 207 to study the CAN bus. The 207’s CAN bus system was sub-divided in to three separate buses and the “comfort” bus provided all the data he needed. To decode the CAN frames, he used an Arduino, a CAN bus shield and a python script to visualize the data, checking to see which frames changed when he performed certain functions — such as changing volume or putting the gear in reverse, for example.

Adding the camera was the easiest part of the exercise when he found an after-market version specifically meant for his 207 model. The original non-graphical display had to make room for a new HDMI display and a fresh bezel, which cost him much more than the display. Besides displaying the camera image when reversing, the new display also needed to show all of the other entertainment system information. This couldn’t be obtained from the OBD-II port but the CAN bus looked promising, although he couldn’t find any details for his model initially. But with over 2.5 million of the 207’s on the road, it wasn’t long before [Alexandre] hit jackpot in a French University student project who used a 207 to study the CAN bus. The 207’s CAN bus system was sub-divided in to three separate buses and the “comfort” bus provided all the data he needed. To decode the CAN frames, he used an Arduino, a CAN bus shield and a python script to visualize the data, checking to see which frames changed when he performed certain functions — such as changing volume or putting the gear in reverse, for example.