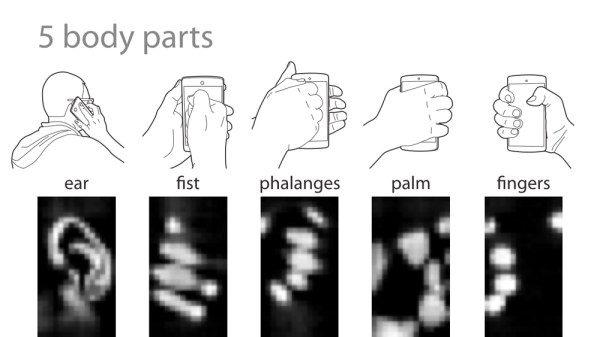

[Christian Holz, Senaka Buthpitiya, and Marius Knaust] are researchers at Yahoo that have created a biometric solution for those unlucky folks that always forget their smartphone PIN codes. Bodyprint is an authentication system that allows a variety of body parts to act as the password. These range from ears to fists.

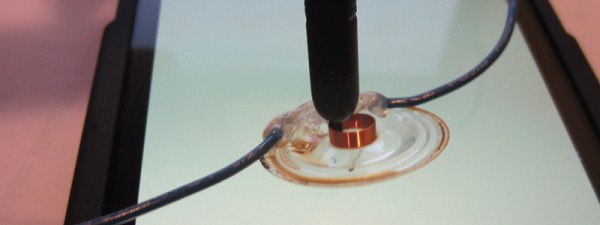

Bodyprint uses the phone’s touchscreen as an image scanner. In order to do so, the researchers rooted an LG Nexus 5 and modified the touchscreen module. When a user sets up Bodyprint, they hold the desired body part to the touchscreen. A series of images are taken, sorted into various intensity categories. These files are stored in a database that identifies them by body type and associates the user authentication with them. When the user wants to access their phone, they simply hold that body part on the touchscreen, and Bodyprint will do the rest. There is an interesting security option: the two person authentication process. In the example shown in the video below, two users can restrict file access on a phone. Both users must be present to unlock the files on the phone.

How does Bodyprint compare to capacitive fingerprint scanners? These scanners are available on the more expensive phone models, as they require a higher touchscreen resolution and quality sensor. Bodyprint makes do with a much lower resolution of approximately 6dpi while increasing the false rejection rate to help compensate. In a 12 participant study using the ears to authenticate, accuracy was over 99% with a false rejection rate of 1 out of 13.