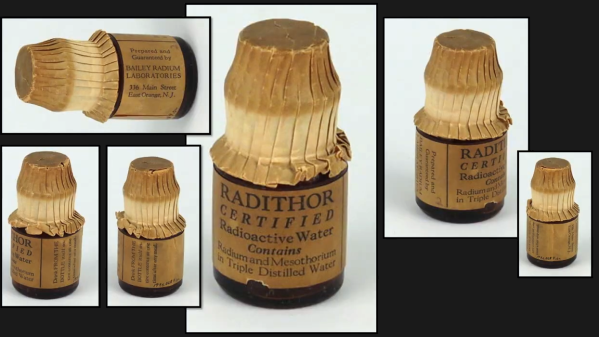

Take a little time to watch the history of Radithor, a presentation by [Adam Blumenberg] into a quack medicine that was exactly what it said on the label: distilled water containing around 2 micrograms of radium in each bottle (yes, that’s a lot.) It’s fascinatingly well-researched, and goes into the technology and societal environment surrounding such a product, which helped play a starring role in the eventual Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938. You can watch the whole presentation in the video, embedded below the break. Continue reading “Radioactive Water Was Once A (Horrifying) Health Fad”

chemistry hacks646 Articles

William Blake Was Etching Copper In 1790

You may know William Blake as a poet, or even as #38 in the BBC’s 2002 poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. But did you know that Blake was also an artist and print maker who made illuminated (flourished) books?

Blake sought to marry his art with his poetry and unleash it on the world. To do so, he created an innovative printing process, which is recreated by [Michael Phillips] in the video after the break. Much like etching a PCB, Blake started with a copper sheet, writing and drawing his works backwards with stopping varnish, an acid-resistant varnish that sticks around after a nitric acid bath. The result was a raised design that could then be used for printing.

Blake was a master of color, using few pigments plus linseed or nut oil to create pastes of many different hues. Rather than use a brayer, Blake dabbed ink gently around the plate, careful not to splash ink or get any in the etched-away areas. As this was bound to happen anyway, Blake would then spend more time wiping out the etched areas than he did applying the ink.

Another of Blake’s innovations was the printing process itself. Whereas traditionally, illuminated texts must be printed in two different workshops, one for the text and the other for the illustrations, Blake’s method of etching both in the same plate of copper made it possible to print using his giant handmade press.

Want to avoid censorship and print your own ‘zines? Why not build a proofing press?.

Making Magnetic Tape From Scratch

The use of magnetic tape and other removable magnetic media is now on the wane, leading to scarcity in some cases where manufacture has ceased. Is it possible to produce new magnetic tape if you don’t happen to own a tape factory? [Nina Kallnina] took the effort to find out.

It’s probably one of those pieces of common knowledge, that magnetic media use iron oxides on their surface, which is the same as rust. But the reality is somewhat more complex, as there is more than one iron oxide. We follow [Nina] through this voyage of discovery in a Mastodon thread, as she tries first iron filings, the rust, and finally pure samples of the two iron oxides Fe3O4 and Fe2O3. She eventually achieves a working tape with a mixture of Fe2O3 and iron powder, though its performance doesn’t match manufactured tape. It turns out that there are two allotropes of Fe2O3, and she leaves us as she’s trying to make the one with better magnetic properties.

These results look promising, and while there is evidently a very long way to go before a home-made magnetic coating could replicate the exacting demands of for example a hard drive platter it’s evident that there is something in pursuing this path.

This may be the first time we’ve seen tape manufacture, but we’ve certainly seen extreme measures taken to rejuvenate old tapes.

Custom Fume Hood For Safe Electroless Plating

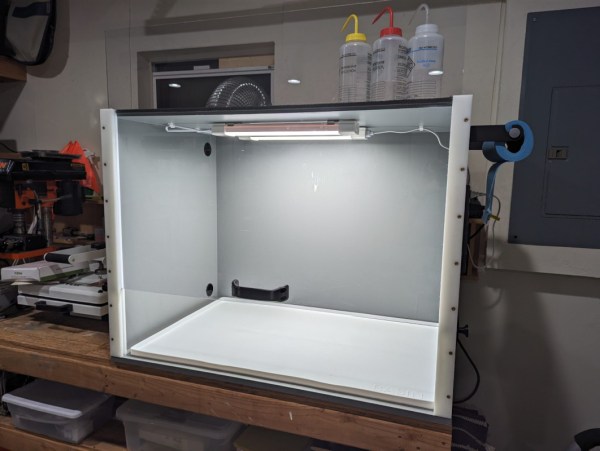

There are plenty of chemical processes that happen commonly around the house that, if we’re really following safety protocols to the letter, should be done in a fume hood. Most of us will have had that experience with soldering various electronics, especially if we’re not exactly sure where the solder came from or how old it is. For [John]’s electroless plating process, though, he definitely can’t straddle that line and went about building a fume hood to vent some of the more harmful gasses out of a window.

This fume hood is pretty straightforward and doesn’t have a few of the bells and whistles found in commercial offerings, but this process doesn’t really require things like scrubbing or filtering the exhaust air so he opted to omit these pricier and more elaborate options. What it does have, though, is an adjustable-height sash, a small form factor that allows it to easily move around his shop, and a waterproof, spill-collecting area in the bottom. The enclosure is built with plywood, allowing for openings for an air inlet, the exhaust ducting, and a cable pass-through, and then finished with a heavy-duty paint. He also included built-in lighting and when complete, looks indistinguishable from something we might buy from a lab equipment supplier.

While [John] does admit that the exhaust fan isn’t anything special and might need to be replaced more often than if he had gone with one that was corrosion-resistant, he’s decided that the cost of this maintenance doesn’t outweigh the cost of a specialized fan. He also notes it’s not fire- or bomb-proof, but nothing he’s doing is prone to thermal anomalies of that sort. For fume hoods of all sorts, we might also recommend adding some automation to them so they are used any time they’re needed.

Continue reading “Custom Fume Hood For Safe Electroless Plating”

Spuds Lend A Hand In The Darkroom

If film photography’s your thing, the chances are you may have developed a roll or two yourself, and if you’ve read around on the subject it’s likely you’ll have read about using coffee, beer, or vegetable extracts as developer. There’s a new one to us though, from [cm.kelsall], who has put the tater in the darkroom, by making a working developer with potatoes as the active ingredient.

The recipe follows a fairly standard one, with the plant extract joined by some washing soda and vitamin C. The spuds are liquidised and something of a watery smoothie produced, which is filtered and diluted for the final product. It’s evidently not the strongest of developers though, because at 20 Celcius it’s left for two hours to gain an acceptable result.

The chemistry behind these developers usually comes from naturally occurring phenols in the plant, with the effectiveness varying with their concentration. They’re supposed to be better for the environment than synthetic developers, but sadly those credentails are let down somewhat by there not being a similar green replacement for the fixer, and the matter of a load of silver ions in the resulting solutions. Still, it’s interesting to know that spuds could be used this way, and it’s something we might even try ourselves one day.

We’ve even had a look at the coffee process before.

Rock Salt May Lead The Way To Better Batteries

The regular refrain here when it comes to announcements of new battery chemistries hailed as potentially miraculous is that if we had a pound, dollar, or Euro for each one we’ve heard, by now we’d be millionaires. But still they keep coming, and it’s inevitable that there will one or two that break through the practicality barrier and really do deliver on their promise. Which brings us tot he story which has come our way today, the suggestion that something as simple as rock salt could triple the energy density of a lithium-ion vehicle battery.

The research led from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory started around the use of cobalt in the battery cathode, an expensive and finite resource with the added concern of being in large part a conflict mineral from the Democratic Republic of Congo. Cobalt is used in the cathodes because its oxide crystals form a stable layered structure into which the lithium ions can percolate. Alternative layered-structure metal oxides perform less well in retaining the lithium ions, making them unsuccessful substitutes. It seems that the three-dimensional structure of a rock salt crystal performs up to three times better than any layered oxide, which is where the excitement comes from.

Of course, if it were that simple we’d all be using three-times-more-powerful, half-price 18650s right now, which of course we aren’t. The challenge comes in making a rock salt cathode which both holds the lithium ions, and keeps that property reliably over the thousands of charge cycles needed for a real-world application. This one may yet be anther dollar on that metaphorical pile, but it just might give us the batteries we’ve been looking for.

Then again, when you’re looking at exciting battery chemistry, why limit yourself to lithium?

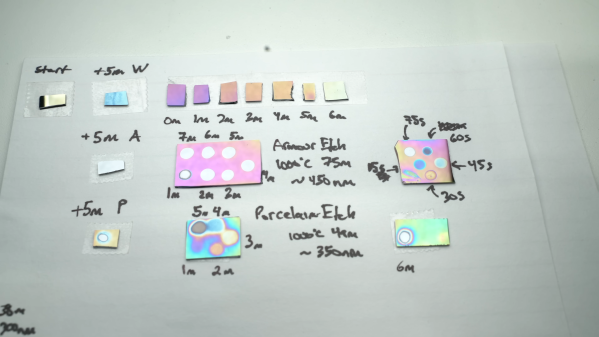

Testing Oxide Etchants For The Home Semiconductor Fab

Building circuits on a silicon chip is a bit like a game of Tetris — you have to lay down layer after layer of different materials while lining up holes in the existing layers with blocks of the correct shape on new layers. Of course, Tetris generally doesn’t require you to use insanely high temperatures and spectacularly toxic chemicals to play. Or maybe it does; we haven’t played the game in a while, so they might have nerfed things.

Luckily, [ProjectsInFlight] doesn’t treat his efforts to build semiconductors at home like a game — in fact, the first half of his video on etching oxide layers on silicon chips is devoted to the dangers of hydrofluoric acid. As it turns out, despite the fact that HF can dissolve your skin, sear your lungs, and stop your heart, as long as you use a dilute solution of the stuff and take proper precautions, you should be pretty safe around it. This makes sense, since HF is present in small amounts in all manner of consumer products, many of which are methodically tested in search of a practical way to remove oxides from silicon, which [ProjectsInFlight] has spent so much effort recently to learn how to deposit. But such is the ironic lot of a chip maker.

Three products were tested — rust remover, glass etching cream, and a dental porcelain etching gel — against a 300 nm silicon dioxide layer. Etch speed varied widely, from rust remover’s 10 nm/min to glass etching cream’s blazing 240 nm/min — we wonder if that could be moderated by thinning the cream out with a bit of water. Each solution had pros and cons; the liquid rust remover was cheap easy to handle and clean up, while the dental etching gel was extremely easy to deposit but pretty expensive.

The good news was that everything worked, and each performed differently enough that [ProjectsInFlight] now has a range of tools to choose from. We’re looking forward to seeing what’s next — looks like it’ll be masking techniques.

Continue reading “Testing Oxide Etchants For The Home Semiconductor Fab”