[Prof. Edwin Hwu] of the Technical University of Denmark wrote in with a call for contributions to special edition of the open-access scientific journal Biosensors. Along the way, he linked in videos from three talks that he’s given on hacking consumer electronics gear for biosensing and nano-scale printing. Many of them focus on clever uses of the read-write head from a Blu-ray disc unit (but that’s not all!) and there are many good hacks here.

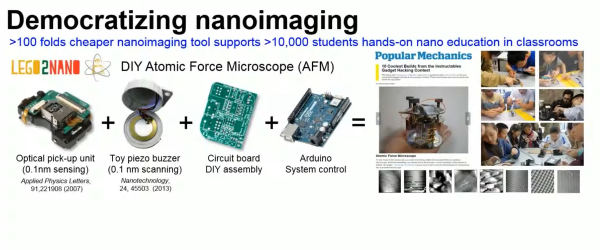

For instance, this video on using the optical pickup for the optics in an atomic force microscope (AFM) is bonkers. An AFM resolves features on the sub-micrometer level by putting a very sharp, very tiny probe on the end of a vibrating arm and scanning it over the surface in question. Deflections in the arm are measured by reflecting light off of it and measuring their variation, and that’s exactly what these optical pickups are designed to do. In addition to phenomenal resolution, [Dr. Hwu’s] AFM can be made on a shoestring budget!

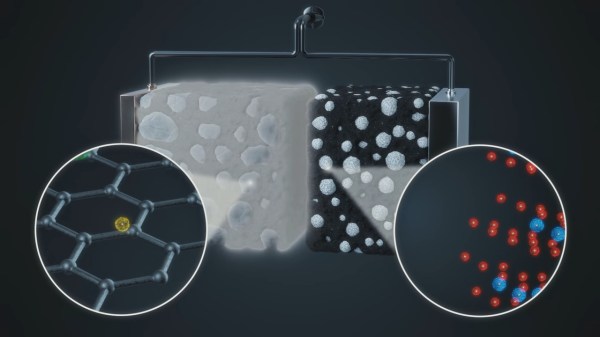

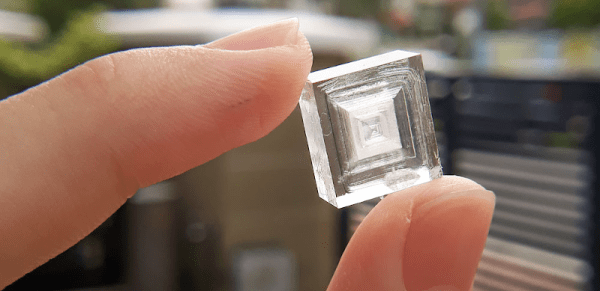

Speaking of AFMs, check out his version that’s based on simple piezo discs in this video, but don’t neglect the rest of the hacks either. This one is a talk aimed at introducing scientists to consumer electronics hacking, so you’ll absolutely find yourself nodding your heads during the first few minutes. But then he documents turning a DVD player into a micro-strobe for high speed microfluidics microscopy using a wireless “spy camera” pen. And finally, [Dr. Hwu’s] lab has also done some really interesting work into nano-scale 3D printing, documented in this video, again using the humble Blu-ray drive, both for exposing the photopolymer and for spin-coating the disc with medium. Very clever!

If you’re doing any biosensing science hacking, be sure to let [Dr. Hwu] know. Or just tear into that Blu-ray drive that’s collecting dust in your closet.