When you’re looking at blueprints today, chances are pretty good that what you’re seeing is anything but blue. Most building plans, diagrams of civil engineering projects, and even design documents for consumer products never even make it to paper, let alone get rendered in old-fashioned blue-and-white like large-format prints used to produced. And we think that’s a bit of a shame.

Luckily, [Brian Haidet] longs for those days as well, so much so that he built this large-format cyanotype camera to create photographs the old-fashioned way. Naturally, this is one of those projects where expectations must be properly scaled before starting; after all, there’s a reason we don’t go around taking pictures with paper soaked in a brew of toxic chemicals. Undaunted by the chemistry, [Brian] began his journey with simple contact prints, with Sharpie-marked transparency film masking the photosensitive paper, made from potassium ferricyanide, ammonium dichromate, and ammonium iron (III) oxalate, from the UV rays of the sun. The reaction creates the deep, rich pigment Prussian Blue, contrasting nicely with the white paper once the unexposed solution is washed away.

[Brian] wanted to go beyond simple contact prints, though, and the ridiculously large camera seen in the video below is the result. It’s just a more-or-less-lightproof box with a lens on one end and a sheet of sensitized paper at the other. The effective ISO of the “film” is incredibly slow, leading to problematically long exposure times. Coupled with the distortion caused by the lens, the images are — well, let’s just say unique. They’ve got a ghostly quality for sure, and there’s a lot to be said for that Prussian Blue color.

We’ve seen cyanotype chemistry used with UV lasers before, and large-format cameras using the collodion process. And we wonder if [Brian]’s long-exposure process might be better suited to solargraphy.

Continue reading “Cocktail Of Chemicals Makes This Blueprint Camera Unique”

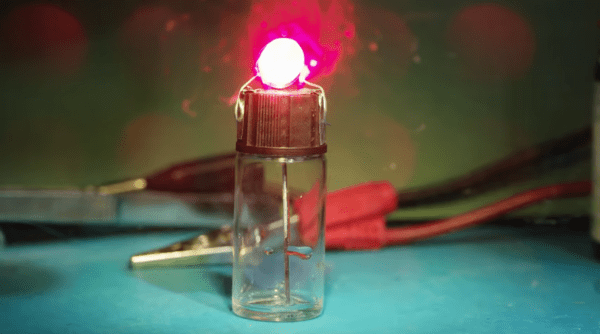

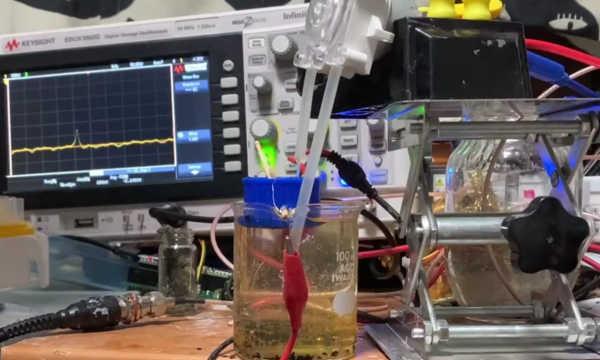

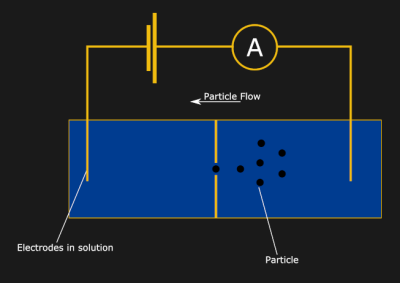

Now, drop an insulating divider in the middle of the container, and the current will stop flowing. Finally, poke a small hole (or nanopore) in the divider. Huzzah! The current is flowing again… but how does this let us measure particle sizes? Well, now think about a tiny particle moving through the hole in the divider. As the particle passes through, the hole will be partially blocked, and the current flow will be partially interrupted. It turns out, the resulting dip in current is proportional to the volume of the particle — a fun property known as the

Now, drop an insulating divider in the middle of the container, and the current will stop flowing. Finally, poke a small hole (or nanopore) in the divider. Huzzah! The current is flowing again… but how does this let us measure particle sizes? Well, now think about a tiny particle moving through the hole in the divider. As the particle passes through, the hole will be partially blocked, and the current flow will be partially interrupted. It turns out, the resulting dip in current is proportional to the volume of the particle — a fun property known as the