If you were building a recreation of the James Watt micrometer, where would you start? If you’re [rasp], the answer would be: “Spend a year trying to find the best way to make etched brass discs.” Luckily for us, he’s ready to share that information with the rest of the world. While it’s rather unlikely anyone else is working on this specific project, the methods he details for getting museum-quality results on brass are absolutely fascinating.

The process starts with sanding down the bare brass and applying a layer of clear packing tape to the metal. [rasp] then covers the piece with LaserTape, which is a special tape designed to make laser-cut masks for sandblasting. But the masking principle works just as well for painting or chemical etching.

The process starts with sanding down the bare brass and applying a layer of clear packing tape to the metal. [rasp] then covers the piece with LaserTape, which is a special tape designed to make laser-cut masks for sandblasting. But the masking principle works just as well for painting or chemical etching.

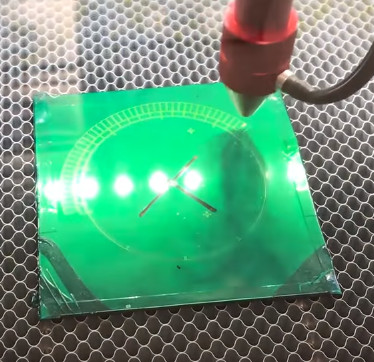

With the LaserTape in place, the piece is then put into the laser and the mask is cut out. Once cut, there’s the tedious task of peeling off all the cut pieces of tape, which [rasp] does with a dental pick. Once the pieces are pulled off, the brass is ready for its acid bath.

Anyone who’s etched their own PCB with ferric chloride will recognize these next steps. The piece is put into the acid bath and agitated every 10 minutes or so. It’s interesting to note that [rasp] places the piece in the bath upside-down, using little 3D printed “feet” to suspend the brass sheet off the bottom of the container. This allows the debris from the etching process to fall down and away from the piece. After about an hour out in the sun, the piece is pulled out of the bath and carefully washed off.

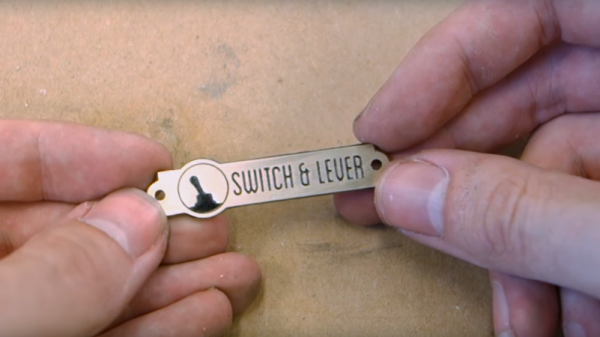

Once clean off, the piece is sprayed with black spray paint to darken up the etched areas. The moment of truth comes when the paint has dried and the layers of tape are carefully peeled back to reveal the etching. [rasp] then wet sands the piece with 1000 and 2000 grit paper, and a final pass with polishing compound brighten up the surface to a mirror-like shine. It’s quite a bit of manual labor, but the end result really is spectacular.

Once clean off, the piece is sprayed with black spray paint to darken up the etched areas. The moment of truth comes when the paint has dried and the layers of tape are carefully peeled back to reveal the etching. [rasp] then wet sands the piece with 1000 and 2000 grit paper, and a final pass with polishing compound brighten up the surface to a mirror-like shine. It’s quite a bit of manual labor, but the end result really is spectacular.

In the video after the break, [rasp] breaks down the entire process, including the additional machine work required to turn these brass plates into functional components of the final machine. As an added bonus, he even includes a lot of his failed attempts in an effort to keep others from making the same mistakes. Something we love to see here at Hackaday.

The process used here is similar to the snazzy brass name plates we showed earlier in the year, and has even been done without a laser using photoresist.

[via /r/DIY]