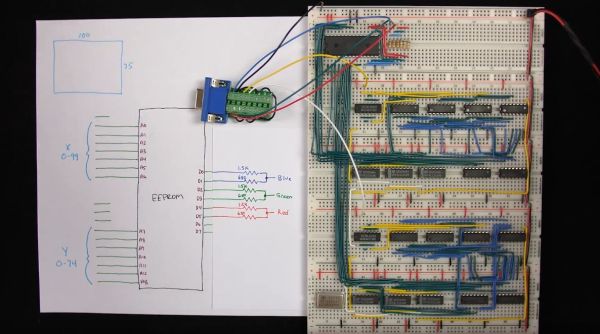

[Ben Eater] is back with the second part of his video series on building a simple video card that can output 200×600 pixels to a display with nothing but a VGA connection, a handful of 74-logic chips and a 10 MHz crystal. In this installment we see how he uses nothing but an EEPROM and a handful of resistors to get an image onto the screen.

The interesting part is in how the image data is encoded into the EEPROM, since it has to be addressable by the same timing circuit as what is being used for the horizontal and vertical timing. By selecting the relevant inputs that’d make a valid address, and by doubling the size of each pixel a few times, a 100 x 75 pixel image can be encoded into the EEPROM and directly addressed using this timing circuit.

The output from the EEPROM itself not fed directly into the monitor, as the VGA interface expects a 0 V to 0.7 V signal on each RGB pin, indicating the brightness. To get more than three colors out of this setup, [Ben] builds up a simple 2-bit DAC that allows for two bits per channel, meaning four brightness levels per color channel or 64 colors effectively.

See the video after the link for the full details. While pretty close to perfect, a small issue remains at the end in the forms of black vertical lines. These are caused by a timing issue in the circuit, with comments on the YouTube video suggesting various other potential fixes. Have you breadboarded your own version yet to debug this issue before [Ben]’s next video comes out?

Continue reading “Pushing Pixels To A Display With VGA Without A PC”