The modern oscilloscope is truly a marvelous instrument, being a computer with a high-speed analogue front end which can deliver the function of an oscilloscope alongside that of a voltmeter and a frequency counter. They don’t cost much, and having one on your bench gives you an edge unavailable in a previous time. That’s not to dismiss older CRT ‘scopes though, the glow of a phosphor trace has illuminated many a fault finding procedure. These older instruments can even be pretty simple, as [Mircemk] demonstrates with a small home-made example that we have to admit to rather liking.

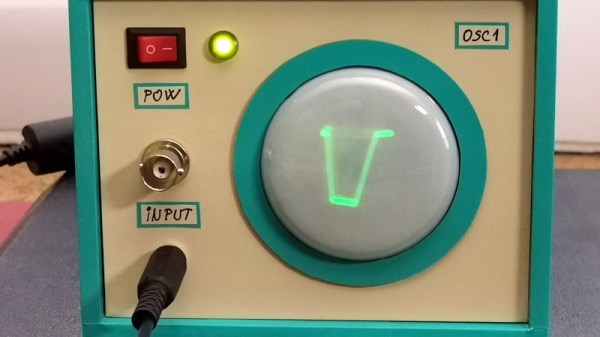

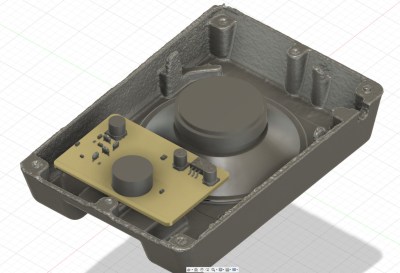

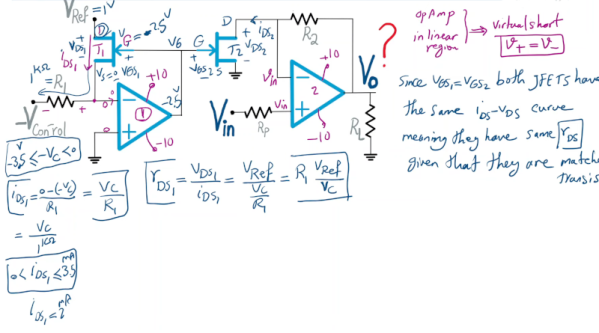

At its heart is a small 5 cm round CRT tube, with an off-the-shelf buck converter supplying the HT, a neon lamp relaxation oscillator supplying the timebase, and a set of passive components conditioning the signal to the deflection plates. The whole thing runs from 12 V and fits in a neat case. It has one huge flaw in that there is no trigger circuit, and sadly this compromises its usefulness as an instrument. Our understanding of a neon oscillator is a little rusty but we’re guessing the two-terminal neon lamp would have to be replaced by one of the more exotic gas-filled tubes with more electrodes, of which one takes the trigger pulse.

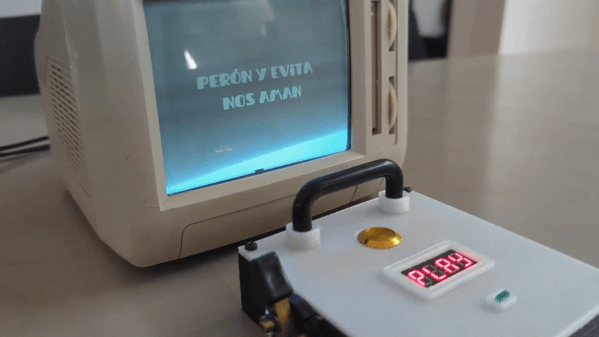

Even without a trigger it’s still a neat device, so take a look at it. Perhaps surprisingly we’ve seen few CRT ‘scopes made from scratch here at Hackaday, but never fear, here’s one used as an audio visualiser.