Many years ago [ScorchWorks] built an electrical-discharge machining tool (EDM) and recently decided to write about it. And there’s a video embedded after the break.

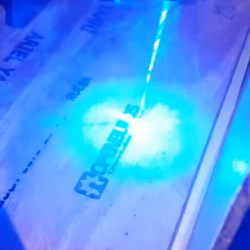

The build is based on the designs described in the book “Build an EDM” by Robert Langolois. An EDM works by creating lots of little electrical discharges between an electrode in the desired shape and a material underneath a dielectric solvent bath. This dissolves the material exactly where the operator would like it dissolved. It is one of the most precise and gentle machining operations possible.

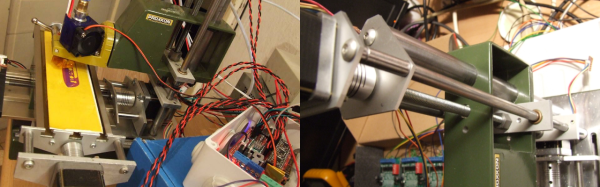

His EDM is built mostly out of found parts. The power supply is a microwave oven transformer rewired with 18 gauge wire to drop the voltage to sixty volts instead of the oven’s original boost to 1.5kV. The power resistor comes from a dryer element robbed from a unit sitting beside the road. The control board was etched using a hand traced schematic on the copper with a Sharpie.

The linear motion element are two square brass tubes, one sliding inside the other. A stepper motor slowly drives the electrode into the part. Coolant is pumped through the electrode which is held by a little 3D printed part.

The EDM works well, and he has a few example parts showing its ability to perform difficult cuts. Things such as a hole through a razor blade., a small hole through a very small piece of thick steel, and even a hole through a magnet.

Continue reading “Homemade EDM Can Cut Through Difficult Materials Like Magnets With Ease”

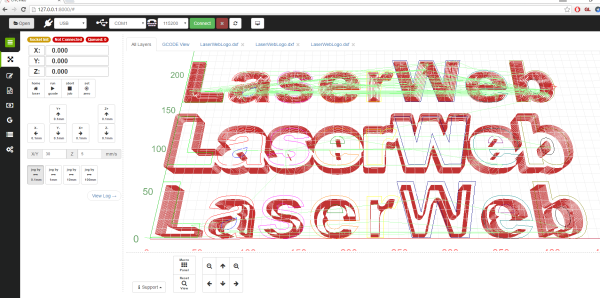

LaserWeb3 supports different controllers and the machines they might be connected to – whether they are home-made systems, CNC frames equipped with laser diode emitters (such as retrofitted 3D printers), or one of those affordable blue-box 40W Chinese lasers with the proprietary controller replaced by something like a

LaserWeb3 supports different controllers and the machines they might be connected to – whether they are home-made systems, CNC frames equipped with laser diode emitters (such as retrofitted 3D printers), or one of those affordable blue-box 40W Chinese lasers with the proprietary controller replaced by something like a