As an electronics rookie, one of the first things they tell you when they teach you about logic gates is, “You can make everything from a combination of NAND gates”. There usually follows a demonstration of simple AND, OR, and XOR gates made from NAND gates, and maybe a flip-flop or two. Then you move on, when you want a logic function you use the relevant device that contains it, and the nugget of information about NAND gates recedes to become just another part of your electronics general knowledge.

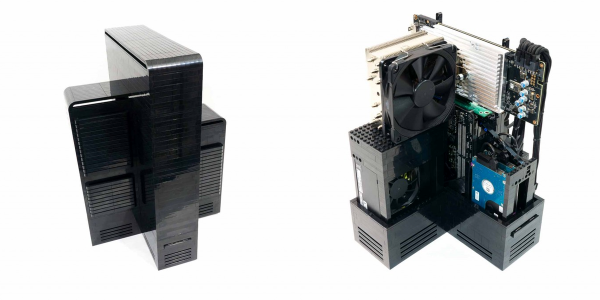

Not [Alexander Shabarshin] though. He’s set himself the task of creating an entire CPU solely from NAND gates, and he’s using 74F00 chips to give a hoped-for 1MIPS performance. His design has an 8-bit data bus but a 4-bit ALU, and an impressive 2-stage pipeline and RISC instruction set which sets it apart from the computers most of us had when 74-series logic was a much more recent innovation. So far he has completed PCBs for a D-type flip-flop and a one-bit ALU, four of which will work in parallel in the final machine

Unsurprisingly, we have maintained a keen interest in TTL computers here at Hackaday for a very long time. You might say that we have featured so many for the subject to deserve a review article of its own. There is the ASAP-3, the Magic-1, the Duo Basic, the Apollo181, the unnamed CPU made by [Donn Stewart], the BMOW, and a clone of the Apollo Guidance Computer. But what sets [Alexander’s] project aside from all these fine machines is his bare-metal NAND-only design. The other 74-series CPU designers have had the full range of devices such as the 74181 ALU at their disposal. By studying the building blocks at this most fundamental level a deeper understanding can be gained of the inner workings of parts normally represented just as black boxes.

One of the briefs for writing a Hackaday article is that if the subject makes the writer stop and read rather than skim over it then it is likely to do so for the reader too. This project may not yet have delivered a working CPU, but its progress so far is interesting enough for an in-depth read. Definitely one to watch.