How better to work on Open Source projects than to use a Libre computing device? But that’s a hard goal to accomplish. If you’re using a desktop computer, Libre software is easily achievable, though keeping your entire software stack free of closed source binary blobs might require a little extra work. But if you want a laptop, your options are few indeed. Lucky for us, there may be another device in the mix soon, because [Lukas Hartmann] has just about finalized the MNT Reform.

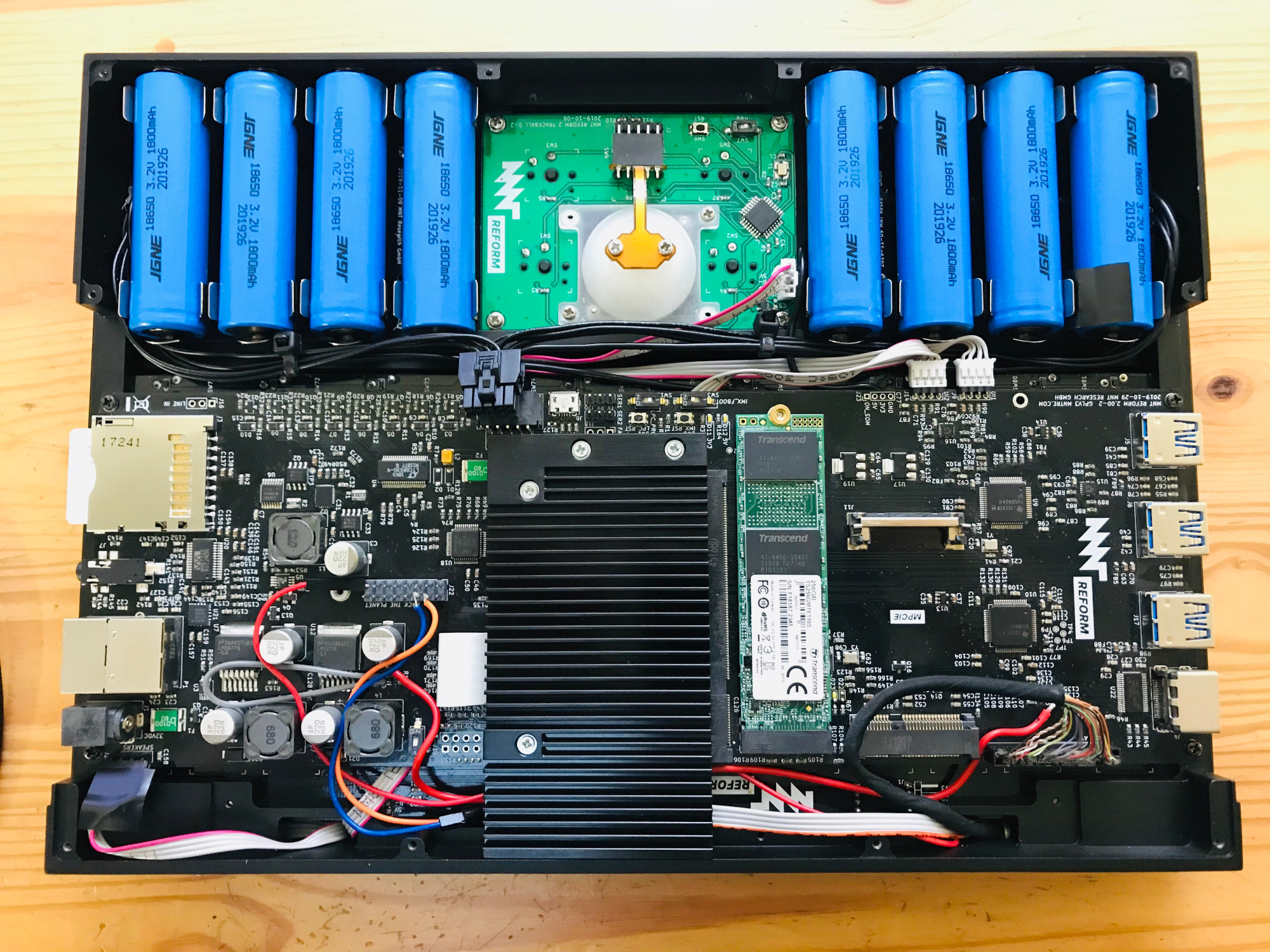

Since we started eagerly watching the Reform a couple years ago the hardware world has kept turning, and the Reform has improved accordingly. The i.MX6 series CPU is looking a little peaky now that it’s approaching end of life, and the device has switched to a considerably more capable – but no less free – i.MX8M paired with 4 GB of DDR4 on a SODIMM-shaped System-On-Module. This particular SOM is notable because the manufacturer freely provides the module schematics, making it easy to upgrade or replace in the future. The screen has been bumped up to a 12.5″ 1080p panel and steps have been taken to make sure it can be driven without blobs in the graphics pipeline.

Since we started eagerly watching the Reform a couple years ago the hardware world has kept turning, and the Reform has improved accordingly. The i.MX6 series CPU is looking a little peaky now that it’s approaching end of life, and the device has switched to a considerably more capable – but no less free – i.MX8M paired with 4 GB of DDR4 on a SODIMM-shaped System-On-Module. This particular SOM is notable because the manufacturer freely provides the module schematics, making it easy to upgrade or replace in the future. The screen has been bumped up to a 12.5″ 1080p panel and steps have been taken to make sure it can be driven without blobs in the graphics pipeline.

If you’re worried that the chassis of the laptop may have been left to wither while the goodies inside got all the attention, there’s no reason for concern. Both have seen substantial improvement. The keyboard now uses the Kailh Choc ultra low profile mechanical switches for great feel in a small package, while the body itself is milled out of aluminum in five pieces. It’s printable as well, if you want to go that route. All in all, the Reform represents a heroic amount of work and we’re extremely impressed with how far the design has come.

Of course if any of the above piqued your interest full electrical, mechanical and software sources (spread across a few repos) are available for your perusal; follow the links in the blog post for pointers to follow. We’re thrilled to see how production ready the Reform is looking and can’t wait to hear user reports as they make their way into to the wild!

Via [Brad Linder] at Liliputing.