Last last month, a post from the relatively obscure Good e-Reader claimed that Amazon would finally allow the Kindle to read EPUB files. The story was picked up by all the major tech sites, and for a time, there was much rejoicing. After all, it was a feature that owners have been asking for since the Kindle was first released in 2007. But rather than supporting the open eBook format, Amazon had always insisted in coming up with their own proprietary formats to use on their readers. Accordingly, many users have turned to third party programs which can reliably convert their personal libraries over to whatever Amazon format their particular Kindle is most compatible with.

Native support for EPUB would make using the Kindle a lot less of a hassle for many folks, but alas, it was not to be. It wasn’t long before the original post was updated to clarify that Amazon had simply added support for EPUB to their Send to Kindle service. Granted this is still an improvement, as it represents a relatively low-effort way to get the open format files on your personal device; but in sending the files through the service they would be converted to Amazon’s KF8/AZW3 format, the result of which may not always be what you expected. At the same time the Send to Kindle documentation noted that support for AZW and MOBI files would be removed later on this year, as the older formats weren’t compatible with all the features of the latest Kindle models.

If you think this is a lot of unnecessary confusion just to get plain-text files to display on the world’s most popular ereader, you aren’t alone. Users shouldn’t have to wade through an alphabet soup of oddball file formats when there’s already an accepted industry standard in EPUB. But given that it’s the reality when using one of Amazon’s readers, this seems a good a time as any for a brief rundown of the different ebook formats, and a look at how we got into this mess in the first place.

Continue reading “Kindle, EPUB, And Amazon’s Love Of Reinventing Wheels”

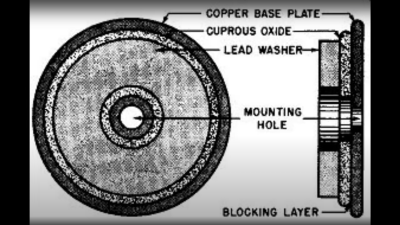

based not upon silicon or germanium, but copper. Copper (I) Oxide is a naturally occurring P-type semiconductor, which can be easily constructed by heating a copper sheet in a flame, and scraping off the outer layer of Copper (II) Oxide leaving the active layer below. Simply making contact to a piece of steel is sufficient to complete the device.

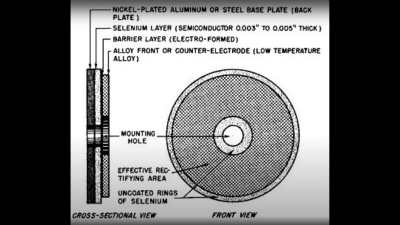

based not upon silicon or germanium, but copper. Copper (I) Oxide is a naturally occurring P-type semiconductor, which can be easily constructed by heating a copper sheet in a flame, and scraping off the outer layer of Copper (II) Oxide leaving the active layer below. Simply making contact to a piece of steel is sufficient to complete the device. as the Selenium rectifier, based on the properties of a Cadmium Selenide – Selenium interface, which forms an NP junction, albeit one that can’t handle as much power as good old copper. One final device, which was a bit of an improvement upon the original CuO rectifiers, was based upon a stack of Copper Sulphide/Magnesium metal plates, but they came along too late. Once we discovered the wonders of germanium and silicon, it was consigned to the history books before it really saw wide adoption.

as the Selenium rectifier, based on the properties of a Cadmium Selenide – Selenium interface, which forms an NP junction, albeit one that can’t handle as much power as good old copper. One final device, which was a bit of an improvement upon the original CuO rectifiers, was based upon a stack of Copper Sulphide/Magnesium metal plates, but they came along too late. Once we discovered the wonders of germanium and silicon, it was consigned to the history books before it really saw wide adoption.