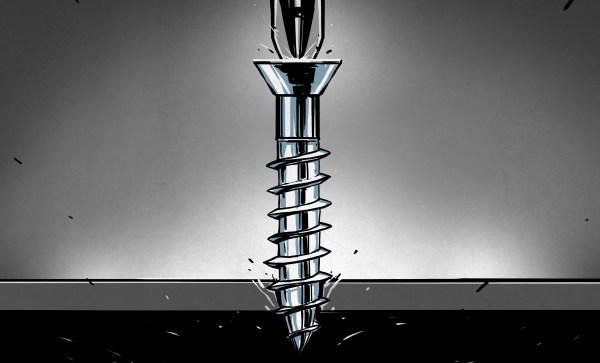

Have you ever wondered how many threads a nut needs to be secure? [Hydraulic Press Channel] decided to find out, using some large hardware and a hydraulic press. The method was simple. He took a standard nut and cut the center out of it to have nuts with fewer threads than the full nut. Then it was on to the hydraulic press.

As you might expect, a single-thread nut gave way pretty quickly at about 10,000 kg. Adding threads, of course, helps. No real surprise, but it is nice to see actual characterization with real numbers. It is also interesting to watch metal hardware bend like cardboard at these enormous pressures.

In the end, he removed threads from the bolts to get a better test and got some surprising results. Examining the failure modes is also interesting.

In the end, he removed threads from the bolts to get a better test and got some surprising results. Examining the failure modes is also interesting.

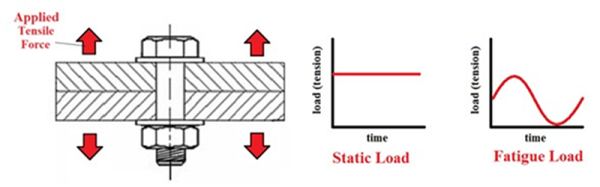

Honestly, we aren’t sure how valid some of the results were, but it was interesting watching the thread stripping and the catastrophic failures of the samples in the press. It seems like to do this right, you need to try a variety of assemblies and maybe even use different materials to see if all the data fit with the change in the number of threads. We expect the shape of the threads also makes a difference.

Still, an interesting video. We always enjoy seeing data generated to test theories and assumptions. We think of bolts and things as pretty simple, but there’s a surprising amount of technology that goes into their design and construction.

Continue reading “Hydraulic Press Channel Puts Nuts To The Test” →