There was a time when any hi-fi worth its salt had a little row of sliders on its front panel, a graphic equalizer. On a hi-fi these arrays of variable gain notch filters were little more than a fancy version of a tone control, but in professional audio and PA systems they are used with many more bands to precisely equalise a venue and remove any unwanted resonances.

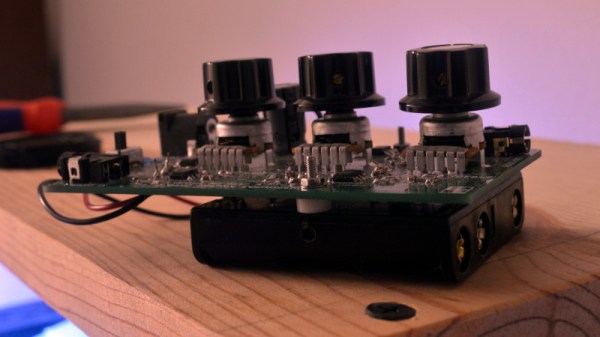

On modern hi-fi the task is performed in software, but [Grant Giesbrecht] wanted an analogue equalizer more in the scheme of those fancy tone controls than the professional devices. His project makes for a fascinating foray into analogue filter design, as well as an understanding of how an equalizer combines multiple filters. Unexpectedly their outputs are not mixed because it proves surprisingly difficult to ensure all the filters have the same gain, instead they are in series with the signal path passing through all filters.

The resulting equalizer is neatly built upon a PCB with a 4-AA-cell power supply, and makes for a self-contained audio component. Unexpectedly such analogue equalizer have been few and far between here at Hackaday so it’s particularly pleasing to see. We’re more used to graphical displays for off-the-shelf devices.

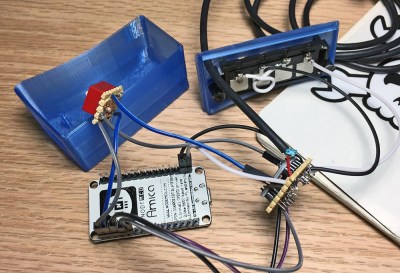

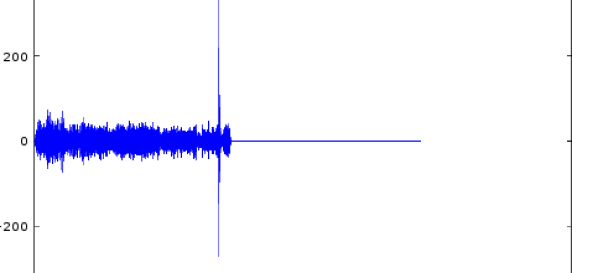

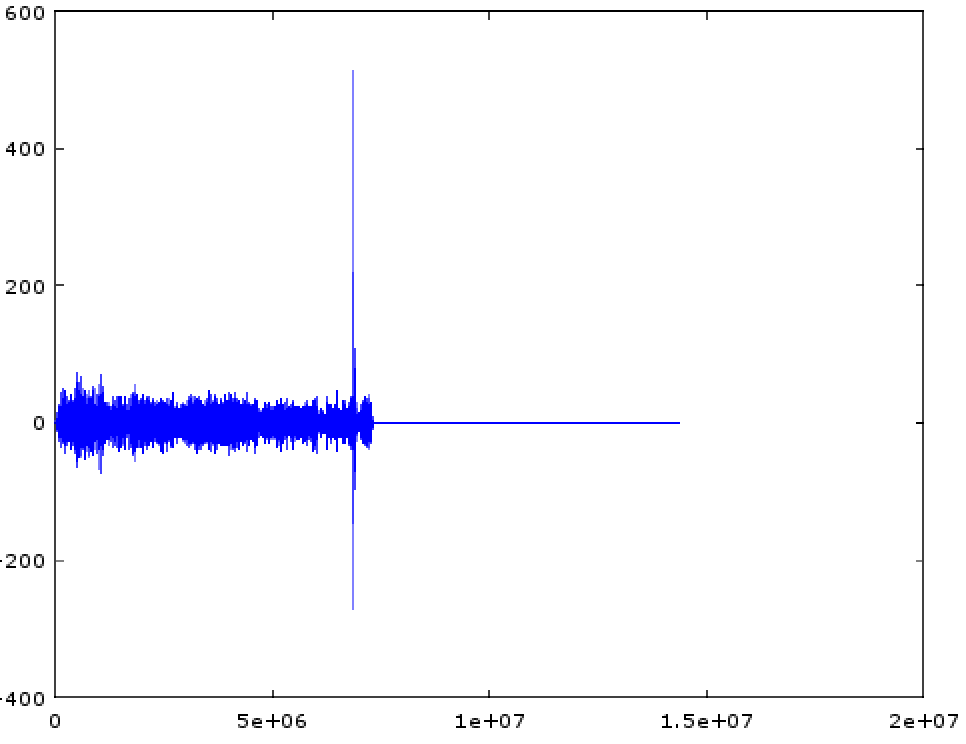

[tomek] was aware of this hip knowledge domain called Digital Signal Processing but hadn’t done any of it themselves. Like many algorithmic problems the first step was to figure out the fastest way to bolt together a prototype to prove a given technique worked. We were as surprised as [tomek] by how simple this turned out to be. Fundamentally it required a single function – cross-correlation – to measure the similarity of two data samples (audio files in this case). And it turns out that

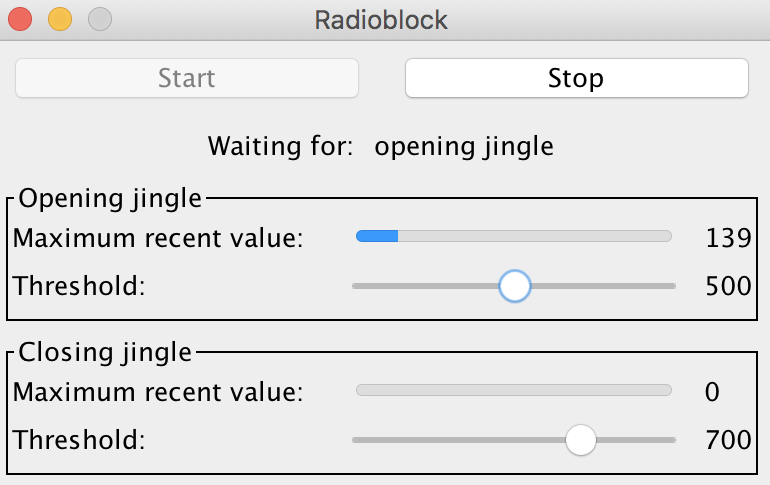

[tomek] was aware of this hip knowledge domain called Digital Signal Processing but hadn’t done any of it themselves. Like many algorithmic problems the first step was to figure out the fastest way to bolt together a prototype to prove a given technique worked. We were as surprised as [tomek] by how simple this turned out to be. Fundamentally it required a single function – cross-correlation – to measure the similarity of two data samples (audio files in this case). And it turns out that  At this point all that was left was packaging it all into a one click tool to listen to the radio without loading an entire analysis package. Conveniently Octave is open source software, so [tomek] was able to dig through its sources until they found the bones of the critical xcorr() function. [tomek] adapted their code to pour the audio into a circular buffer in order to use an existing Java FFT library, and the magic was done. Piping the stream out of ffmpeg and into the ad detector yielded events when the given ad jingle samples were detected.

At this point all that was left was packaging it all into a one click tool to listen to the radio without loading an entire analysis package. Conveniently Octave is open source software, so [tomek] was able to dig through its sources until they found the bones of the critical xcorr() function. [tomek] adapted their code to pour the audio into a circular buffer in order to use an existing Java FFT library, and the magic was done. Piping the stream out of ffmpeg and into the ad detector yielded events when the given ad jingle samples were detected.