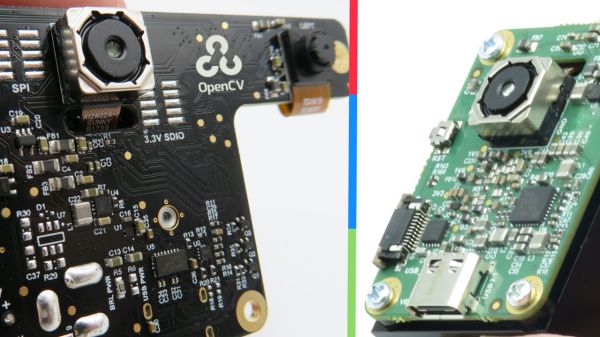

Cameras are getting smarter and more capable than ever, able to run embedded machine vision algorithms and pull off tricks far beyond what something like a serial camera and microcontroller board would be capable of, and the upcoming Vizy aims to be even smarter and easier to use yet. Vizy is the work of Charmed Labs, and this isn’t their first foray into accessible machine vision. Charmed Labs are the same folks behind the Pixy and Pixy 2 cameras. Vizy’s main goal is to make object detection and classification easy, with thoughtful hardware features and a browser-based interface.

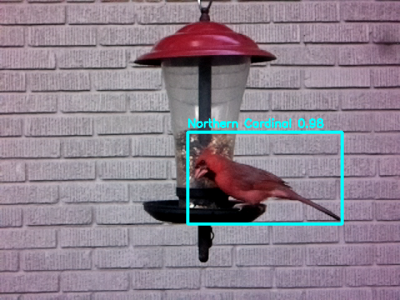

The usual way to do machine vision is to get a USB camera and run something like OpenCV on a desktop machine to handle the processing. But Vizy leverages a Raspberry Pi 4 to provide a tightly-integrated unit in a small package with a variety of ready-to-run applications. For example, the “Birdfeeder” application comes ready to take snapshots of and identify common species of bird, while also identifying party-crashers like squirrels.

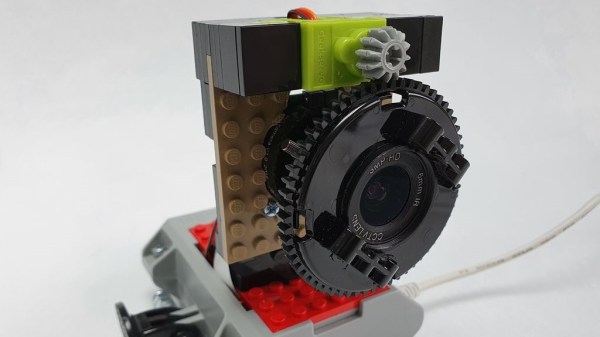

The demonstration video on their page shows off using the built-in high-current I/O header to control a sprinkler, repelling non-bird intruders with a splash of water while uploading pictures and video clips. The hardware design also looks well thought out; not only is there a safe shutdown and low-power mode for the Raspberry Pi-based hardware, but the lens can be swapped and the camera unit itself even contains an electrically-switched IR filter.

Vizy has a Kickstarter campaign planned, but like many others, Charmed Labs is still adjusting to the changes the COVID-19 pandemic has brought. You can sign up to be notified when Vizy launches; we know we’ll be keen for a closer look once it does. Easier machine vision is always a good thing, because it helps free people to focus on clever ideas like machine vision-based tool alignment.