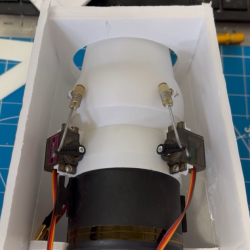

An EDF (electric duct fan) is a motor that basically functions as a jet engine for RC aircraft. They’re built for speed, but to improve maneuverability (and because it’s super cool) [johnbecker31] designed a 3D-printable method of adjusting the EDF’s thrust on demand.

The folks at Flite Test released a video in which they built [john]’s design into a squat tester jet that adjusts thrust in sync with the aircraft’s control surfaces, as you can see in the header image above. Speaking of control surfaces, you may notice that test aircraft lacks a rudder. That function is taken over by changing the EDF’s thrust, although it still has ailerons that move in sync with the thrust system.

EDF-powered aircraft weren’t really feasible in the RC scene until modern brushless electric motors combined with the power density of lithium-ion cells changed all that. And with electronics driving so much, and technology like 3D printers making one-off hardware accessible to all, the RC scene continues to be fertile ground for all sorts of fascinating experimentation. Whether it’s slapping an afterburner on an EDF or putting an actual micro jet engine on an RC car.