Join us on Wednesday, June 9 at noon Pacific for the LED Matrix Hack Chat with Garrett Mace!

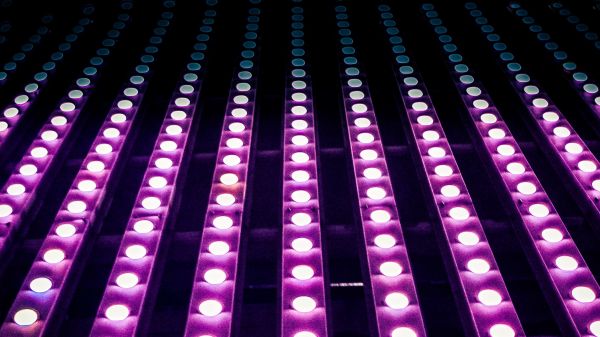

It’s pretty amazing how quickly light-emitting diodes went from physics lab curiosity to a mainstream commodity product made in the millions, if not billions. Everything about LEDs has gotten better, smaller, and cheaper over the years, going from an “any color you want as long as it’s red” phase to all the colors of the rainbow and beyond in a relatively short time. LEDs have worked their way into applications that just didn’t seem likely not that long ago, like architectural lighting, automotive applications, and even immense displays covering billboards, buildings, and sporting venues with multicolor, high-resolution displays.

It’s that latter application that seems to have provided a boon to electronics hobbyists, in the form of cheap and plentiful LED matrix modules. These are easily sourced at the usual places, and with their tightly packed pinpoints that can show any color at any intensity, they have a ton of fun and useful applications for the hacker. But how exactly do you put them to use? Usually the electronics end is pretty straightforward, but some of the math involved in figuring out how to address all these LEDs can be a little mind-bending.

To help us sort all this out, Garrett Mace will drop by the Hack Chat. You’ve probably seen Garrett’s cool LED matrix shades, which have gone through a ton of revisions and are a much-copied fashion accessory among the cool hackers. They look simple, but there are tricks to making them work right, and Garrett will share his secrets. Come with your questions on putting LED matrix modules to work, especially those odd-size modules and strange arrangements that defy simple Cartesian coordinates.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, June 9 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, June 9 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io. You don’t have to wait until Wednesday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.

Legend has it that and engineer working in his father’s barbershop led him to discover not only the first working clock, but also the pipe organ, launching the field of pneumatics in the process. That engineer was named Ctesibius and while his story is mostly forgotten, it shows he has a place as a historical hacker.

Legend has it that and engineer working in his father’s barbershop led him to discover not only the first working clock, but also the pipe organ, launching the field of pneumatics in the process. That engineer was named Ctesibius and while his story is mostly forgotten, it shows he has a place as a historical hacker.