The nearly limitless array of consumer gadgets hackers have shoved the Raspberry Pi into should really come as no surprise. The Pi is cheap, well documented, and in the case of the Pi Zero, incredibly compact. It’s like the thing is begging to get grafted into toys, game systems, or anything else that could use a penguin-flavored infusion.

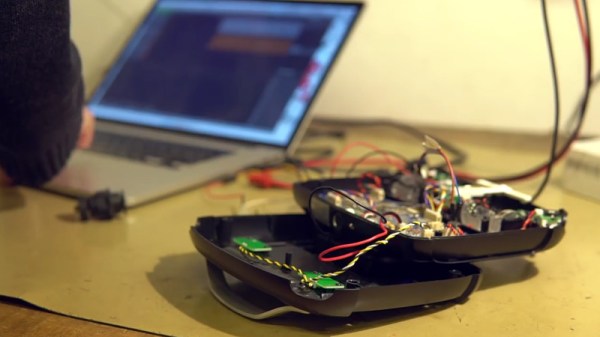

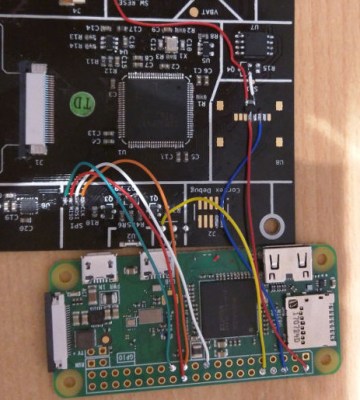

But this particular project takes it to the next level. Rather than just cramming the Pi and a cheap LCD into his Numworks graphing calculator, [Zardam] integrated it into the device so well that you’d swear it was a feature from the factory. By exploiting the fact that the calculator has some convenient solder pads connected to its SPI bus, he was able to create an application which switches the display between the Pi and the calculator at will. With just a press of a button, he’s able to switch between using the stock calculator software and having full access to the internal Pi Zero.

But this particular project takes it to the next level. Rather than just cramming the Pi and a cheap LCD into his Numworks graphing calculator, [Zardam] integrated it into the device so well that you’d swear it was a feature from the factory. By exploiting the fact that the calculator has some convenient solder pads connected to its SPI bus, he was able to create an application which switches the display between the Pi and the calculator at will. With just a press of a button, he’s able to switch between using the stock calculator software and having full access to the internal Pi Zero.

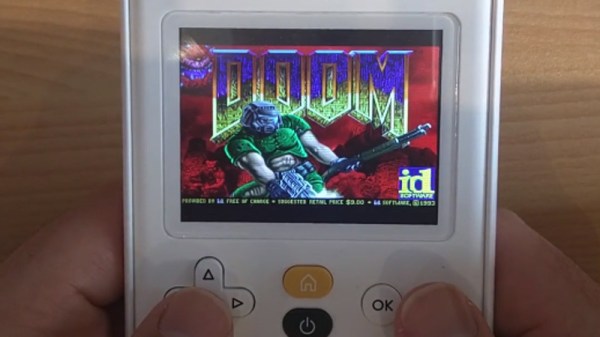

In a very detailed write-up on his site, [Zardam] explains the process of getting the Pi Zero to output video over SPI. The first part of the battle was re-configuring the GPIO pins and DMA controller. After that, there was the small issue of writing a Linux SPI framebuffer driver. Luckily he was able to find some work done previously by [Sprite_TM] which helped him get on the right track. His final driver is able to push 320×240 video at 50 FPS via GPIO, more than enough to kick back with some DOOM.

With video sorted out, he still needed a way to interface the calculator’s keyboard with the Pi. For this, he added a function in his calculator application that echoed the keys pressed to the calculator’s UART port. This is connected to the Pi, where a daemon is listening for key presses. The daemon then generates the appropriate keycodes for the kernel via uinput. [Zardam] acknowledges this part of the system could do with some refinement, but judging by the video after the break, it works well enough for a first version.

We’ve seen the Pi Zero get transplanted into everything from a 56K modem to the venerated Game Boy, and figured nothing would surprise us at this point. But we’ve got to say, this is one of the cleanest and most practical builds we’ve seen yet.

[Thanks to EdS for the tip]

Continue reading “Graphing Calculator Dual Boots With Pi Zero”

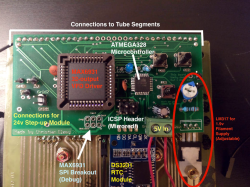

After getting the VFDs lighting up and figuring out the circuitry on the back, [InThePartsBin] decided that a clock was the best thing to build out of it. It was decided that a specialized VFD driver chip was the easiest way to make the thing work, so a MAX6934 was ordered. To give the clock some brains, an ATmega328 was recruited and to keep time, [InThePartsBin] had some DS3231 real-time clock modules left over from a previous project, so they were recruited as well. A daughterboard was designed to sit on the back of the vintage board and hold the ‘328 and the VFD driver chip.

After getting the VFDs lighting up and figuring out the circuitry on the back, [InThePartsBin] decided that a clock was the best thing to build out of it. It was decided that a specialized VFD driver chip was the easiest way to make the thing work, so a MAX6934 was ordered. To give the clock some brains, an ATmega328 was recruited and to keep time, [InThePartsBin] had some DS3231 real-time clock modules left over from a previous project, so they were recruited as well. A daughterboard was designed to sit on the back of the vintage board and hold the ‘328 and the VFD driver chip.