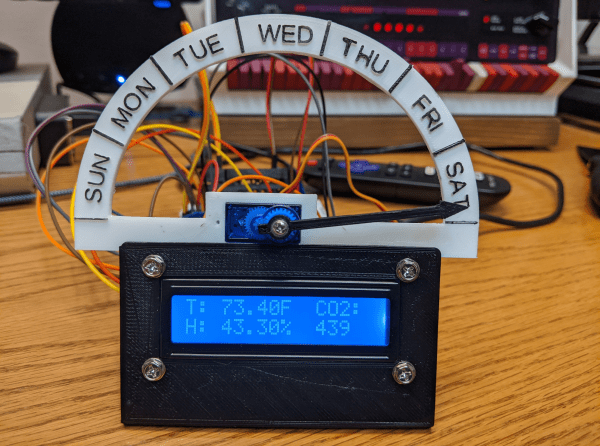

As the world settles into this pandemic, some things are still difficult to mentally reckon, such as the day of the week. We featured a printed day clock a few months ago that used a large pointer to provide this basic psyche-grounding information. In the years since then, [Jeff Thieleke] whipped up a feature-rich remix that adds indoor air quality readings and a lot more.

Like [phreakmonkey]’s original day tripper, an ESP32 takes care of figuring out what day it is and moves a 9 g servo accordingly. [Jeff] wanted a little more visual action, so the pointer moves a tad bit every hour. A temperature/humidity sensor and a separate CO₂ sensor output their readings to an LCD screen mounted under the pointer. Since [Jeff] is keeping this across the basement workshop from the bench, the data is also available from a web server running on the ESP32 via XML and JSON, and the day clock can get OTA updates.

Need a little more specificity than just eyeballing a pointer? Here’s a New Times clock that gives slightly more detail.