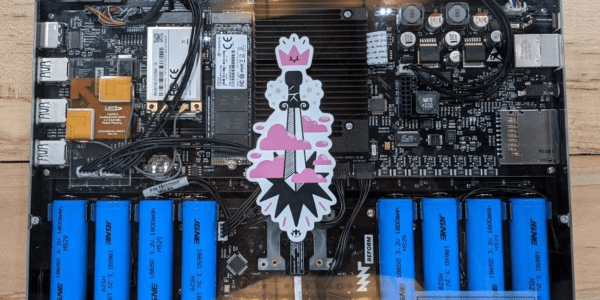

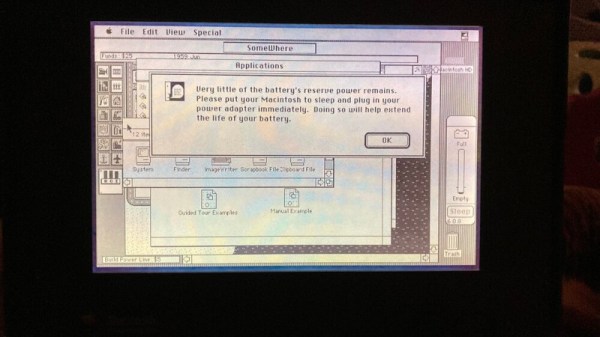

When we met our contact from MNT in the coffee shop, he was quietly working away on his laptop. Jet black and standing thick it was like an encyclopedia that didn’t quite blend in with the sea of silver MacBook lookalikes on the surrounding tables. After going through all the speeds and feeds we eagerly got our 64 piece driver kit out to open it up and see what made this marvel tick, but when the laptop was turned over it became clear that no tools were needed. The entire bottom of the machine was a single rectangle of transparent acrylic revealing everything from sharp white status LEDs on the bare mainboard to individual 18650 LiFePO4 battery cells in a tidy row. In a sense that’s the summary of the entire product: it’s a real laptop you can use to get work done, and every element of it from design to fabrication is completely transparent.

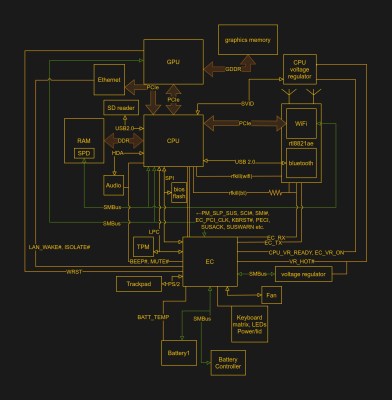

The device pictured here is called the Reform and is designed and manufactured by MNT, a company in Berlin, Germany (note MNT stands for MNT, it’s not an acronym). The Reform is a fully open source laptop which is shipping today and available via distribution through Crowd Supply. If the aesthetic doesn’t make it clear the Reform is an opinionated product designed from the ground up to optimize for free-as-in-freedom: from it’s solid metal chassis to the blob-free GNU/Linux distribution running inside.

We’re here to tell you that we’ve held one, it’s real, and it’s very well built.