The Linux Foundation is a non-profit organization that sponsors the work of Linus Torvalds. Supporting companies include HP, IBM, Intel, and a host of other large corporations. The foundation hosts several Linux-related projects. This month they announced Zephyr, an RTOS aimed at the Internet of Things.

The project stresses modularity, security, and the smallest possible footprint. Initial support includes:

- Arduino 101

- Arduino Due

- Intel Galileo Gen 2

- NXP FRDM-K64F Freedom

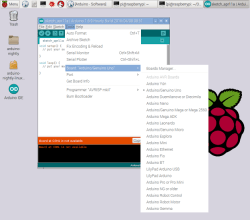

The project (hosted on its own Website) has downloads for the kernel and documentation. Unlike a “normal” Linux kernel, Zephyr builds the kernel with your code to create a monolithic image that runs in a single shared address space. The build system allows you to select what features you want and exclude those you don’t. You can also customize resource utilization of what you do include, and you define resources at compile time.

By default, there is minimal run-time error checking to keep the executable lean. However, there is an optional error-checking infrastructure you can include for debugging.

The API contains the things you expect from an RTOS like fibers (lightweight non-preemptive threads), tasks (preemptively scheduled), semaphores, mutexes, and plenty of messaging primitives. Also, there are common I/O calls for PWM, UARTs, general I/O, and more. The API is consistent across all platforms.

You can find out more about Zephyr in the video below. We’ve seen RTOS systems before, of course. There’s even some for robots. However, having a Linux-heritage RTOS that can target small boards like an Arduino Due and a Freedom board could be a real game changer for sophisticated projects that need an RTOS.

Continue reading “The Internet Of Linux Things” →