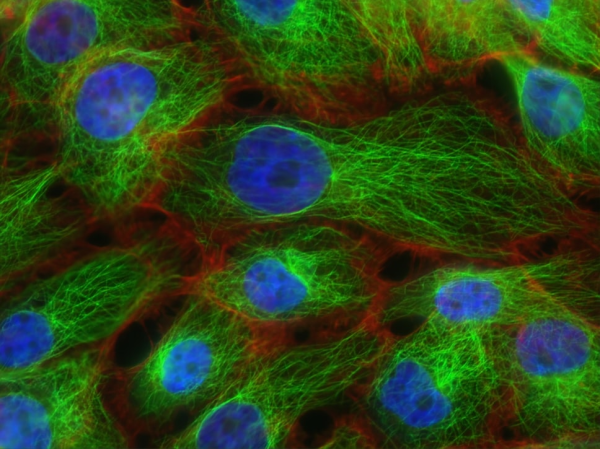

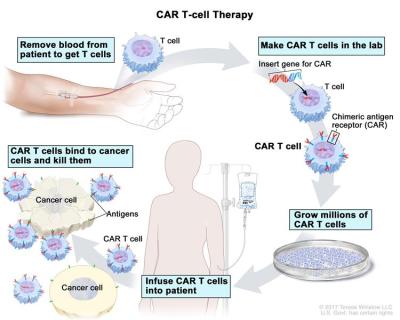

One of the human body’s greatest features is its natural antivirus protection. If your immune system is working normally, it produces legions of T-cells that go around looking for abnormalities like cancer cells just to gang up and destroy them. They do this by grabbing on to little protein fragments called antigens that live on the surface of the bad cells and tattle on their whereabouts to the immune system. Once the T-cells have a stranglehold on these antigens, they can release toxins that destroy the bad cell, while minimizing collateral damage to healthy cells.

This rather neat human trick doesn’t always work, however. Cancer cells sometimes mask themselves as healthy cells, or they otherwise thwart T-cell attacks by growing so many antigens on their surface that the T-cells have no place to grab onto.

Medical science has come up with a fairly new method of outfoxing these crafty cancer cells called CAR T-cell therapy. Basically, they withdraw blood from the patient, extract the T-cells, and replace the blood. The T-cells are sent off to a CRISPR lab, where they get injected with a modified, inactive virus that introduces a new gene which causes the T-cells to sprout a little hook on their surface.

This hook, which they’ve dubbed the chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), allows the T-cell to chemically see through the cancer cells’ various disguises and attack them. The lab multiplies these super soldiers and sends them back to the treatment facility, where they are injected into the patient’s front lines.

Continue reading “CRISPR Could Fry All Cancer Using Newly Found T-Cell”