If you have knee surgery, you can probably count on some physical therapy to go with it. But one thing you might not be able to count on is getting enough attention from your therapist. This was the case with [Vignesh]’s mother, who suffers from osteoarthritis (OA). Her physiotherapist kept a busy schedule and couldn’t see her very often, leaving her to wonder at her rehabilitation progress.

[Vignesh] already had a longstanding interest in bio-engineering and wearables. His mother’s experience led him down a rabbit hole of research about the particulars of OA rehabilitation. He found that less than 35% of patients adhere to the home regimen they were given. While there are a lot of factors at play, the lack of feedback and reinforcement are key components. [Vignesh] sought to develop a simple system for patients and therapists to share information.

The fruit of this labor is Orthosense, an intelligent knee brace system that measures gait angle, joint acoustics, and joint strain. The user puts on the brace, pairs it with a device, and goes through their therapy routine. Sensors embedded in the brace upload their data to the cloud over Bluetooth.

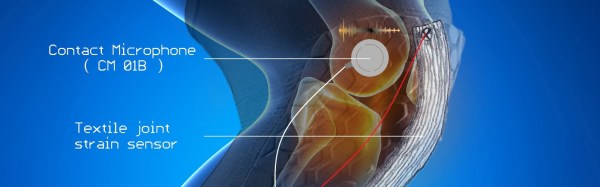

Joint strain is measured by a narrow strip of conductive fabric running down the length of the knee. As the user does their exercises, the fabric stretches and relaxes, changing resistances all the while. The changes are measured against a Wheatstone bridge voltage divider. The knee’s gait angle is measured with an IMU and is calculated relative to the hip angle—this gives a reference point for the data collected by the strain sensor. An electret mic and a sensitive contact mic built for body sounds picks up all the pops and squeaks emitted by the knee. Analysis of this data provides insight into the condition of the cartilage and bones that make up the joint. As you might imagine, unhealthy cartilage is noisier than healthy cartilage.

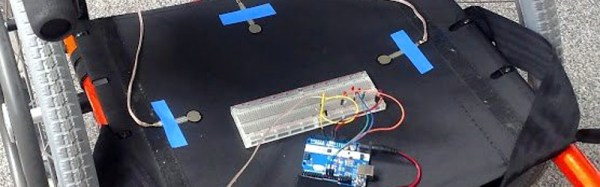

[Vignesh]’s prototype is based the tinyTILE because of the onboard IMU, ADC, and Bluetooth. Since all things Curie are being discontinued, the next version will either use something nRF52832 or a BC127 module and a la carte sensors. [Vignesh] envisions a lot for this system, and we are nodding our heads to all of it.