When we think of 7-segment displays as the ubiquitous LED devices that sprung into popularity in the 1970s. However, numbers have existed for a lot longer than that, and people have wanted to know what the numbers are for quite some time, too. Thus, a variety of technologies were used prior to the LED – such as these magnificent incandescent 7-segment displays shown off by [Fran Blanche].

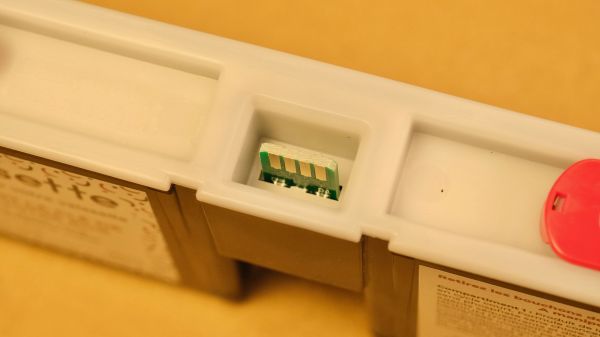

The displays are basic in concept, but we imagine a little frustrating in execution. Electronics was tougher back in the days when valves needed huge voltages and even a basic numerical display drew a load of current. Built to industrial-grade specifications, they’re complete with a big heatsinking enclosure and rugged gold-plated connectors. [Fran] surmises that due to the likely military applications of such hardware, the filaments in the bulbs were likely built in such a way as to essentially last indefinitely. The glow of the individual segments has a unique look versus their LED siblings; free of hotspots and the usual tapered shape on each segment. Instead, the numerals are pleasingly slab-sided for a familiar-but-not-quite aesthetic.

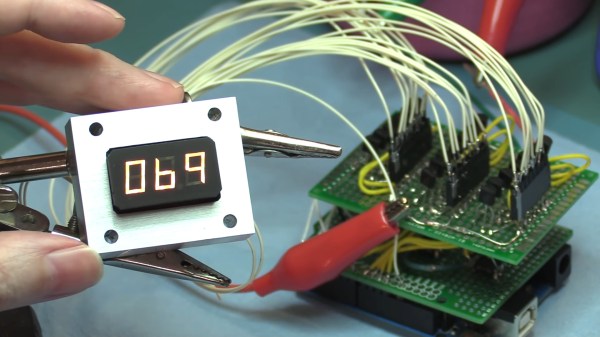

[Fran] demonstrates the display running with a CD4511B BCD-to-7-segment decoder, hooked up with a bunch of 3904 power transistors to get the chip working with filament bulbs instead of LEDs. It’s a little fussy, but the displays run great with the hardware sorted.

We’d love to see these used on a very heavy ridiculous watch; nixies aren’t the only game in town after all. If you do happen to make one, be sure to let us know. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Incandescent 7-Segment Displays Are Awesome”