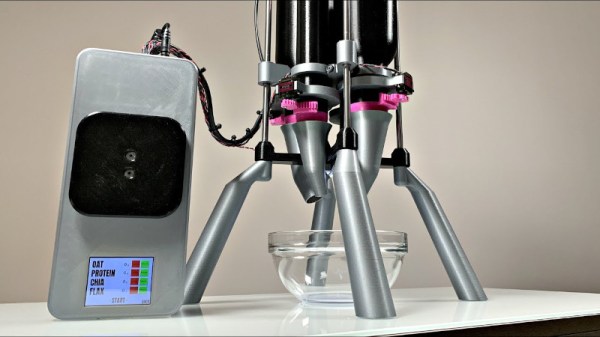

[Elite Worm] follows a strict diet that involves regularly mixing dry ingredients in varying proportions. The task grew tedious, and thus automation became a tantalising prospect. Enter the DIY shaking food dispenser.

The machine has a simple touch screen interface, with an Atmega328P running the show behind the scenes. The user can store a series of profiles, which each correspond to a different mixture of four base ingredients. Dealing with dry ingredients like oats, chia, and flax, shaking is often necessary to get things moving. To achieve this, the rig packs a hefty DC motor up top, which turns an eccentric shaft, shaking the whole rig. Each ingredient hopper has a servo-controlled nozzle, so ingredients can be dispensed in turn, with a load cell in the base measuring the weight delivered.

It’s a neat system, though [Elite Worm] notes that the device shakes just a little too much, and suspects it won’t hold up in the long term. We suspect a less violent, higher frequency vibration might be less hard on the components, but we’re sure there’ll be some quality engineering going into the next build. We’ve seen [Elite Worm]’s work here before, too. Video after the break.