A trebuchet is one of the older machines of war. It’s basically a sling on a frame, with a weight that you can lift up high and which pulls the sling arm over on release. Making one opens up the doors to backyard mayhem, but optimizing one opens up the wonders of physics.

[Tom Stanton] covers just about everything you need to know about trebuchet building in his four-part video series. Indeed, he sums it up in video two: you’ve got some potential energy in the weight, and you want to transfer as much of that as possible to the ball. This implies that the optimal path for the weight would be straight down, but then there’s the axle in the way. The rest, as they say, is mechanical engineering.

Video three was the most interesting for us. [Tom] already had some strange arm design that intends to get the weight partially around the axle, but he’s still getting low efficiencies, so he builds a trebuchet on wheels — the classic solution. Along the way, he takes a ton of measurements with Physlets Tracker, which does video analysis to extract physical measurements. That tip alone is worth the price of admission, but when the ball tops out at 124 mph, you gotta cheer.

In video four, [Tom] plays around with the weight of the projectile and discovers that he’s putting spin on his tennis ball, making it curve in flight. Who knew?

Anyway, all four videos are embedded below. You can probably skip video one if you already know what a trebuchet is, or aren’t interested in [Tom] learning that paying extra money for a good CNC mill bit is worth it. Video two and three are must-watch trebucheting.

We’re a sad to report that we couldn’t find any good trebuchet links on Hackaday to dish up. You’re going to have to settle for a decade-old catapult post or this sweet beer-pong-playing robotic arm. You can help. Submit your trebuchet tips.

Thanks [DC] for this one!

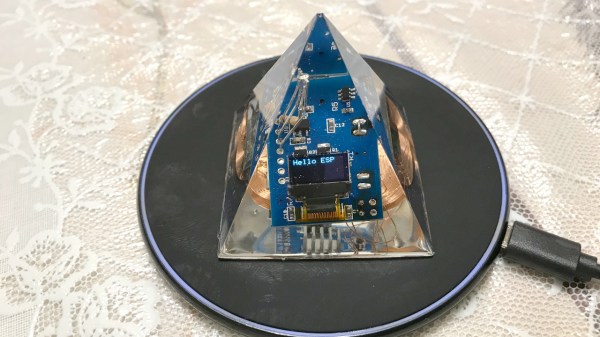

His first works of electronic art were a couple of transistors and some ICs, including an 80386, encased in epoxy. But then he realized that he wanted the electronics to do something interesting. However, once encased in epoxy, how do you keep the electronics powered forever?

His first works of electronic art were a couple of transistors and some ICs, including an 80386, encased in epoxy. But then he realized that he wanted the electronics to do something interesting. However, once encased in epoxy, how do you keep the electronics powered forever?

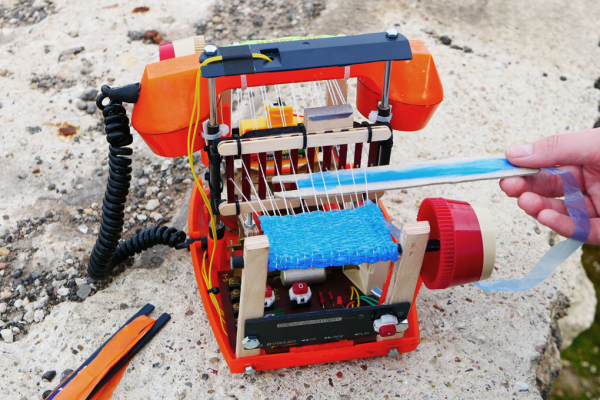

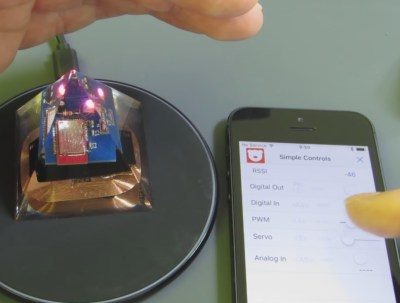

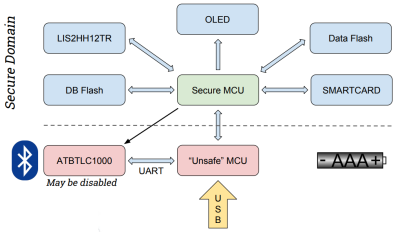

The key to the hardware is the use of a smartcard with proven encryption to store your passwords. Mooltipass is a secure interface between this card and a computer via USB. The new version will be a challenge as it introduces BLE for connectivity with smart phones. To help mitigate security risks, a second microcontroller is added to the existing design to act as a gatekeeper between the secure hardware and the BLE connection.

The key to the hardware is the use of a smartcard with proven encryption to store your passwords. Mooltipass is a secure interface between this card and a computer via USB. The new version will be a challenge as it introduces BLE for connectivity with smart phones. To help mitigate security risks, a second microcontroller is added to the existing design to act as a gatekeeper between the secure hardware and the BLE connection.