A lot of projects get made because someone just has the parts lying around. In this case, [Ed Nisley] got given a nice 8×8 RGB LED matrix, and needed something to display. [Ed] details the transformation of stuff-lying-on-the-desk into a unique matrix display for a Geiger counter (which he also presumably had sitting around somewhere). The result is a lightshow that’s as random as radioactive decay, and that’s pretty darn random.

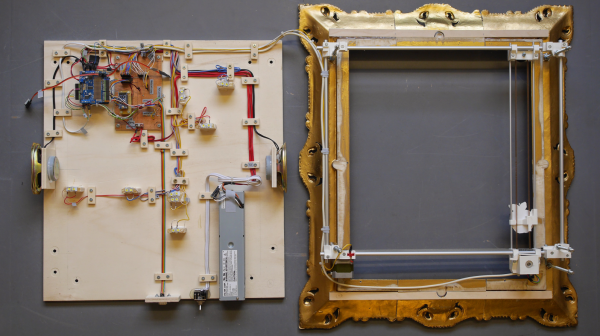

The first post covers the hardware layout. It’s build on protoboard, but ends up looking a lot nicer than our projects because [Ed] spent some time hiding the shift-register ICs and row-driver transistors underneath the matrix itself, which was nicely socketed above. A sweet touch is the use of SMT resistors soldered upright underneath the board to save space. Cute.

The first post covers the hardware layout. It’s build on protoboard, but ends up looking a lot nicer than our projects because [Ed] spent some time hiding the shift-register ICs and row-driver transistors underneath the matrix itself, which was nicely socketed above. A sweet touch is the use of SMT resistors soldered upright underneath the board to save space. Cute.

The second post covers the circuit design, and is worth a look if you’re new to driving many LEDs from a minimum number of microcontroller pins. There are eight rows, and three colors each for eight LEDs per row. Without using shift registers, this would require 8*8*8*8 = way too many pins to control. If you want a worked example of how to do this with just four microcontroller pins, have a look. (Spoiler: cascaded shift registers driven by the AVR’s hardware SPI peripheral.)

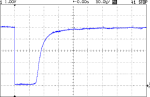

The third post starts to flesh out the software. [Ed] settled on seven colors (and off) for the display, so the matrix’s total state can be crammed into just 32 bytes, which fits nicely in even a tiny microcontroller, much less the gargantuan ATmega328. Wrapping this all up in an array of structs and providing a couple of helper functions makes quick work of the software side. The addition of a sync pulse to trigger an oscilloscope at the end of a row is a nice touch.

Next up is the Geiger counter interface software post. When a radioactive decay event is detected, the code reads out the time in milliseconds and uses that as the source of randomness. To whiten the noise, the times are run through a simple hash function: the Jenkins hash (link). This hash function was new to us and seems pretty useful for quick-and-dirty microcontroller applications.

Next up is the Geiger counter interface software post. When a radioactive decay event is detected, the code reads out the time in milliseconds and uses that as the source of randomness. To whiten the noise, the times are run through a simple hash function: the Jenkins hash (link). This hash function was new to us and seems pretty useful for quick-and-dirty microcontroller applications.

The last post details pre-loading the matrix on startup and running a test sequence that blinks each LED to make sure they’re all working. Using a single random value to seed a software pseudo-random number generator ensures that it will (almost) never start off with the same display twice.

Phswew! That’s a lot of well-documented writeup of a well-polished project! Hope it inspires you to dig out something cool from your junk drawer and build.