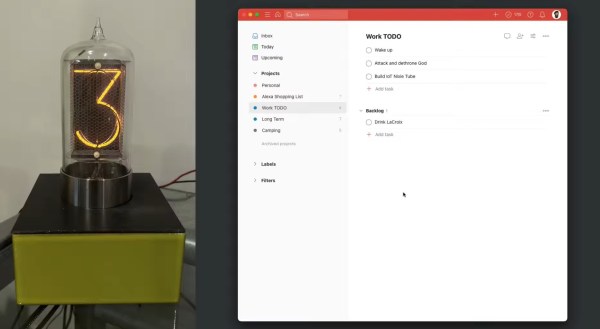

For busy people, keeping track of all the tasks on your to-do list can be a daunting task in itself. Luckily there’s software to help you keep organized, but it’s always nice to have a physical artifact as well. Inspired by some beautiful nixie clock designs, [Bertrand Fan] decided to build a nixie indicator that tells him how many open items are on his to-do list, giving a shot of instant gratification as it counts down with each finished task.

The task-management part of this project is a on-line tool called Todoist. This program comes with a useful Web API that allows you to connect it your own software projects and exchange data. [Bert] wrote some code to extract the number of outstanding tasks from his to-do list and send it to an ESP8266 D1 Mini that drives the nixie tube. Mindful of the security implications of letting such a device connect directly to the internet, he set up a Mac Mini to act as a gateway, connecting to the ESP8266 through WiFi and to the Todoist servers through a VPN.

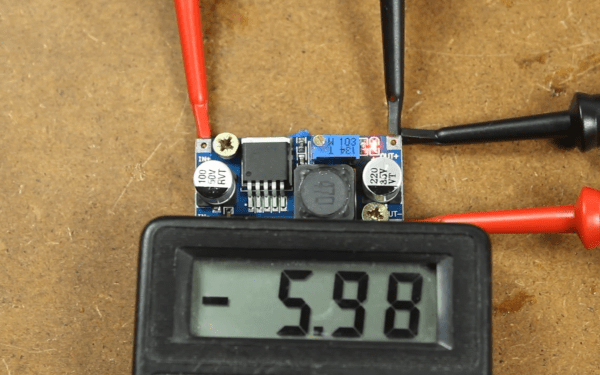

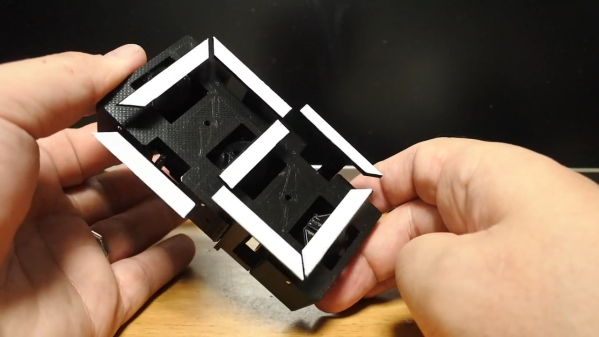

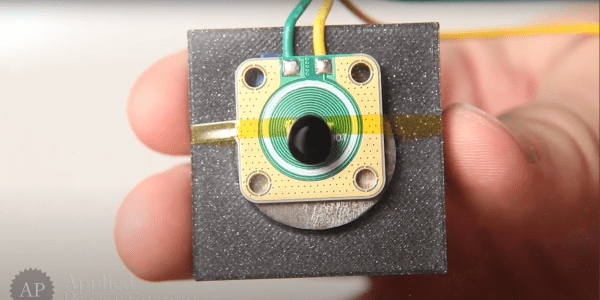

The little ESP board is sitting in a 3D-printed case, together with the nixie driver circuits and a socket to hold the tube. A ceramic tile glued to the front gives it a bit more of a sturdy, luxury feel to match the shiny glass and metal display device. The limitations of the nixie tube restrict the number of tasks indicated to nine, but we imagine this might actually be useful to help prevent [Bert] from overloading himself with too many tasks. After all, what’s the point of having this device if you can’t reach that satisfying “zero” at the end of the day?

Although nowadays nixie tubes are mostly associated with fancy clocks, we’ve seen them used in a variety of other uses, such as keeping track of 3D-printer filament, adding a display to a 1940s radio, or simply displaying nothing useful at all.

Continue reading “Nixie Tube Indicator Tells You How Many Tasks You’ve Got Left To Do”