Technology marches on at a rapid pace, but in many fields much love remains for older hardware. While still highly capable, there’s often room for improvement thanks to components made available in the intervening years. After longing for his SY-77 synthesiser of the 90s, [Mark] sourced a tired SY-99, the next model up in the line – and set to work on some upgrades.

The SY-99 relied on floppy disks for storage, but the mechanical drives are now difficult to maintain, to say nothing of the unreliability of floppy media. [Mark] installed a SD Card HXC floppy emulator instead, using a Sparkfun SD breakout to neatly install the card slot in the synth’s case. The tired LCD was replaced with a newer model using the same controller, with an LED backlight proving a nice upgrade over the original EL unit.

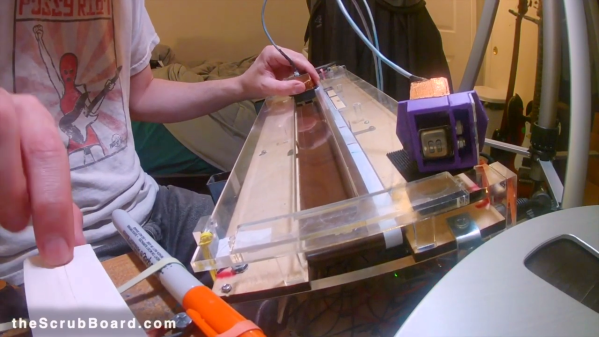

Additionally, [Mark] realised that there was scope to create his own upgrade modules with off-the-shelf SRAM chips. This proves far cheaper than sourcing second-hand Yamaha stock off eBay, and is readily achievable by anyone with a basic understanding of digital logic. The ICs can be had for a few dollars, versus well over $50 for the original cards – if you can even find them. Some labor is involved, but it’s a lot less painful to the wallet.

[Mark]’s work is a great example of how hardware that was once prohibitively expensive can be given greater functionality at a lower cost thanks to new technology. We’ve seen other synths modded too, like this Korg Monotron. If you’ve been tinkering away in a keyboard yourself, be sure to let us know!

[Thanks to CRJEEA] for the tip]