While it might not pack the computational punch you’d usually be looking for in a server platform, you can’t beat how cheap the Raspberry Pi is. As such, it’s at the heart of many a home LAN, serving up files as a network attached storage (NAS) device. But the biggest problem with using the Pi in a NAS is that it doesn’t have any onboard hard drive interface, forcing you to use USB. Not only is this much slower, but doesn’t leave you a lot of options for cleanly hooking up your drives.

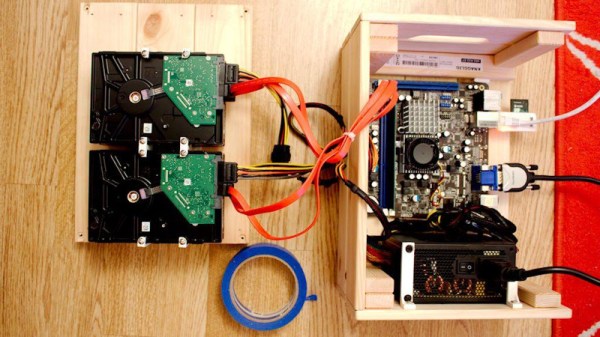

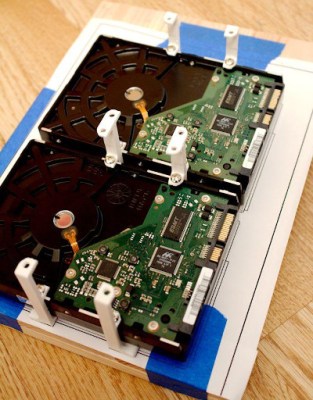

This 3D printable NAS enclosure designed by [Paul-Louis Ageneau] helps address the issue by integrating two drive bays which can accommodate 2.25 inch laptop hard disk drives and their associated IB-AC6033-U3 USB adapters. The drives simply slide into the “rails” designed into the case without the need for additional hardware. There’s even space in the bottom of the case for a USB hub to connect the drives, and a fan on the top of the case to help keep the whole stack cool. It still isn’t perfect, but it’s compact and doesn’t look half bad.

The design is especially impressive as it doesn’t require any supports, an admirable goal to shoot for whenever designing for 3D printing. As an added bonus, the entire case is designed in OpenSCAD and licensed under the GPL v3; making modification easy if you want to tweak it for your specific purposes.

This certainly isn’t the strongest Raspberry Pi enclosure we’ve ever seen, that title would have to go to the ammo case that does double duty as a media streamer, but looks like it would make a great home for that new 3 B+ you’ve got on order.