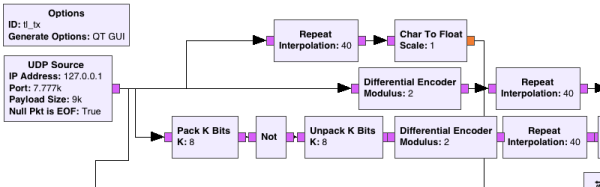

News comes to us this week that the famous HAARP antenna array is to be brought back into service for experiments by the University of Alaska. Built in the 1990s for the US Air Force’s High Frequency Active Auroral Research Program, the array is a 40-acre site containing a phased array of 180 HF antennas and their associated high power transmitters. Its purpose it to conduct research on charged particles in the upper atmosphere, but that hasn’t stopped an array of bizarre conspiracy theories being built around its existence.

The Air Force gave up the site to the university a few years ago, and it is their work that is about to recommence. They will be looking at the effects of charged particles on satellite-to-ground communications, as well as over-the-horizon communications and visible observations of the resulting airglow. If you live in Alaska you may be able to see the experiments in your skies, but residents elsewhere should be able to follow them with an HF radio. It’s even reported that they are seeking reports from SWLs (Short Wave Listeners). Frequencies and times will be announced on the @UAFGI Twitter account. Perhaps canny radio amateurs will join in the fun, after all it’s not often that the exact time and place of an aurora is known in advance.

Tinfoil hat wearers will no doubt have many entertaining things to say about this event, but for the rest of us it’s an opportunity for a grandstand seat on some cutting-edge atmospheric research. We’ve reported in the past on another piece of upper atmosphere research, a plan to seed it with plasma from cubesats, and for those of you that follow our Retrotechtacular series we’ve also featured a vintage look at over-the-horizon radar.

HAARP antenna array picture: Michael Kleiman, US Air Force [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.