It sometimes seems as though antennas and RF design are portrayed as something of a Black Art, the exclusive preserve of an initiated group of RF mystics and beyond the reach of mere mortals. In fact though they have their difficult moments it’s possible to gain an understanding of the topic, and making that start is the subject of a video from [Andreas Spiess]. Entitled “How To Build A Good Antenna”, it uses the design and set-up of a simple quarter-wave groundplane antenna as a handle to introduce the viewer to the key topics.

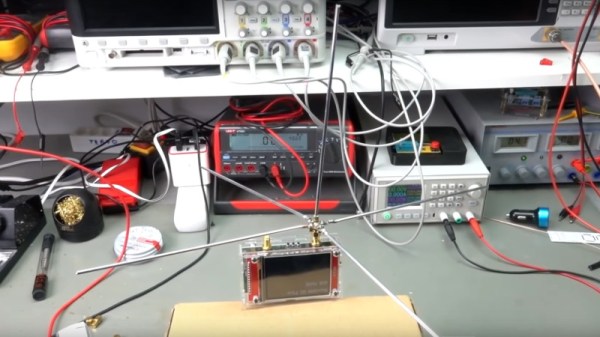

What makes this video a good one is its focus on the practical rather than the theoretical. We get advice on connectors and antenna materials, and we’re introduced to the maths through online calculators rather than extensive formulae. Of course the full calculations are there to be learned by those with an interest, but for many constructors they can be somewhat daunting. We’re shown a NanoVNA as a useful tool in the antenna builder’s arsenal, one which gives a revolutionary window on performance compared to the trial-and-error of previous times. Even the ground plane gets the treatment, with its effect on impedance and gain explored and the emergence of its angle as a crucial factor in performance. We think this approach does an effective job of breaking the mystique surrounding antennas, and we hope it will encourage viewers to experiment further.

If your appetite has been whetted, how about taking a look at a Nano VNA in action?