[Thom Cherryhomes] shared with us an incredible resource for anyone curious about the Coleco Adam, one of the big might-have-been home computers of the 80s. There’s a monstrous 4-hour deep dive video (see the video description for a comprehensive chapter index) that makes a fantastic reference for anyone wanting to see the Coleco Adam and all of its features in action, in the context of 8-bit home computing in the 80s.

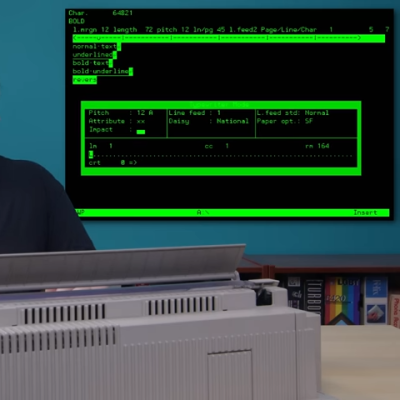

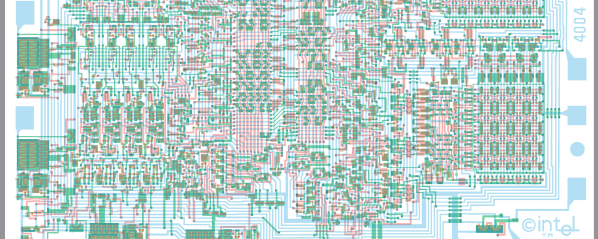

The video is a serious in-depth look at the Adam, providing practical demonstrations of everything in various scenarios. This includes showcasing commercials from the period, detailing the system’s specs and history, explaining the Adam’s appeal, discussing specific features, comparing advertisement promises to real costs, and giving a step-by-step tutorial on how to use the system. All of the talk notes are available as well, providing a great companion to the chapter index.

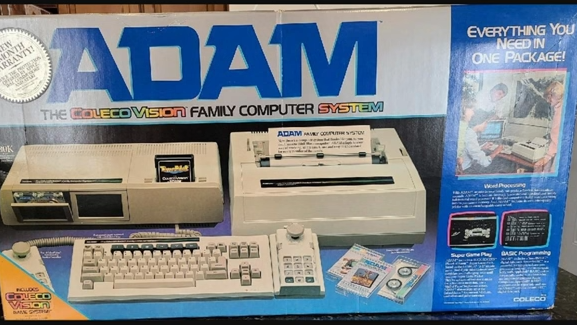

Manufactured by the same Coleco responsible for the ColecoVision gaming console, the Adam had great specs, a great price, and a compelling array of features. Sadly, it was let down badly at launch and Coleco never recovered. However, the Adam remains of interest in the retrocomputing scene and we’ve even seen more than one effort to convert the Adam’s keyboard to USB.

Continue reading “Absolutely Everything About The Coleco Adam, 8-bit Home Computer”