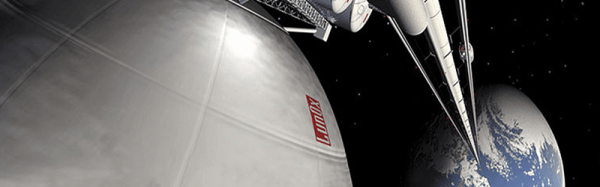

You probably wouldn’t expect to see somebody making astronomical observations during a cloudy day in the center of a dense urban area, but that’s exactly what was happening at the recent 2019 Philadelphia Mini Maker Faire. Professor James Aguirre of the University of Pennsylvania was there demonstrating the particularly compact Mini Radio Telescope (MRT) project built around an old DirecTV satellite dish and a smattering of low-cost components, giving visitors a view of the sky in a way most had never seen before.

Thanks to the project’s extensive online documentation, anyone with a spare satellite dish and a couple hundred dollars in support hardware can build their very own personal radio telescope that’s capable of observing objects in the sky no matter what the time of day or weather conditions are. Even if you’re not interested in peering into deep space from the comfort of your own home, the MRT offers a framework for building an automatic pan-and-tilt directional antenna platform that could be used for picking up signals from orbiting satellites.

Thanks to the project’s extensive online documentation, anyone with a spare satellite dish and a couple hundred dollars in support hardware can build their very own personal radio telescope that’s capable of observing objects in the sky no matter what the time of day or weather conditions are. Even if you’re not interested in peering into deep space from the comfort of your own home, the MRT offers a framework for building an automatic pan-and-tilt directional antenna platform that could be used for picking up signals from orbiting satellites.

With the slow collapse of satellite television in the United States these dishes are often free for the taking, and a fairly common sight on the sidewalk come garbage day. Perhaps there’s even one (or three) sitting on your own roof as you read this, waiting for a new lease on life in the Netflix Era.

Whether it’s to satisfy your own curiosity or because you want to follow in Professor Aguirre’s footsteps and use it as a tool for STEM outreach, projects like MRT make it easier than ever to build a functional DIY radio telescope.

Continue reading “A Miniature Radio Telescope In Every Backyard”