If you’re into amateur rocketry, you pretty quickly outgrow the dinky little Estes motors that they sell in the toy stores. Many hobbyists move on to building their own homebrew solid rocket motors and experimenting with propellant mixtures, but it’s difficult to know if you’re on the right track unless you have a way to quantify the thrust you’re getting. [ElementalMaker] decided he’d finally hit the point where he needed to put together a low-cost test stand for his motors, and luckily for us decided to document the process and the results.

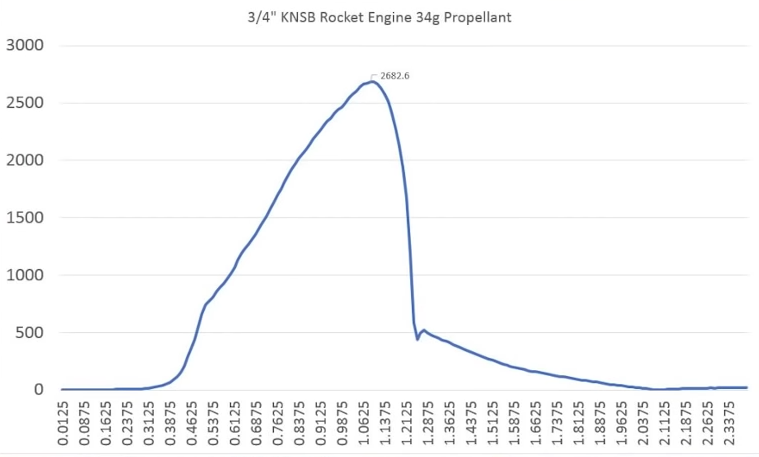

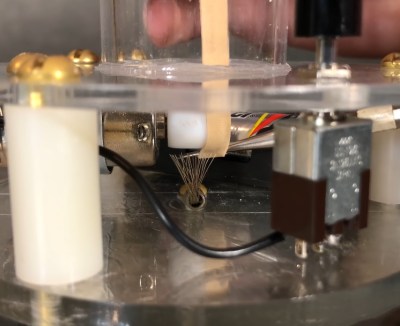

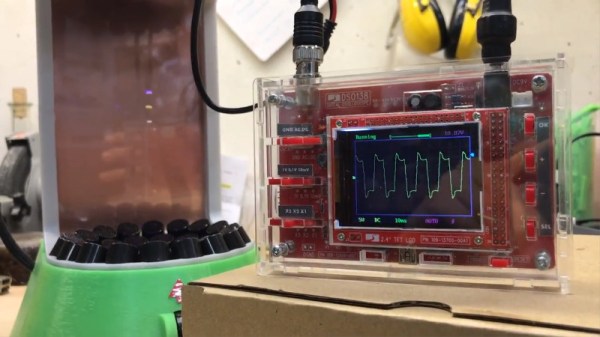

The heart of the stand is a common load cell (the sort of thing you’d find in a digital scale) coupled with a HX711 amplifier board mounted between two plates, with a small section of vertical PVC pipe attached to the topmost plate to serve as a motor mount. This configuration is capable of measuring up to 10 kilograms with an 80Hz sample rate, which is critically important as these type of rocket motors only burn for a few seconds to begin with. The sensor produces hundreds of data points during the short duration of the burn, which is perfect for graphing the motor’s thrust curve over time.

The heart of the stand is a common load cell (the sort of thing you’d find in a digital scale) coupled with a HX711 amplifier board mounted between two plates, with a small section of vertical PVC pipe attached to the topmost plate to serve as a motor mount. This configuration is capable of measuring up to 10 kilograms with an 80Hz sample rate, which is critically important as these type of rocket motors only burn for a few seconds to begin with. The sensor produces hundreds of data points during the short duration of the burn, which is perfect for graphing the motor’s thrust curve over time.

Given such a small window in which to make measurements, [ElementalMaker] didn’t want to leave anything to chance. So rather than manually igniting the motor and triggering the data collection, the stand’s onboard Arduino does both automatically. Pressing the red button on the stand starts a countdown procedure complete with flashing LED, after which a relay is used to energize a nichrome wire “electronic match” stuck inside the motor.

In the video after the break you can see that [ElementalMaker] initially had some trouble getting the Arduino to fire off the igniter, and eventually tracked the issue down to an overabundance of current that was blowing the nichrome wire too fast. Swapping out the big lead acid battery he was originally using with a simple 9V battery solved the problem, and afterwards his first test burns on the stand were complete successes.

If model rockets are your kind of thing, we’ve got plenty of content here to keep you busy. In the past we’ve covered building your own solid rocket motors as well as the electronic igniters to fire them off, and even a wireless test stand that lets you get a bit farther from the action at T-0.

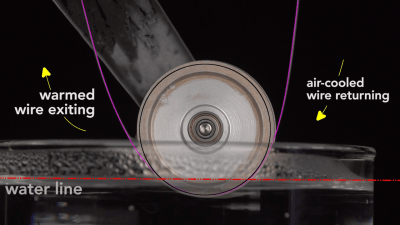

Has this material science excursion bored you to tears yet? That’s why we love [Bill’s] work. He has always done a fantastic job of demystifying common mysticism and this is no different. The video below does a much better job of illustrating what we’ve described above, but also pull out a Nitinol engine for added wow-factor. A straight piece of Nitinol is bent into a loop around two pulleys. The lower pulley is submerged in hot water, causing the Nitinol to want to straighten out, but it loops back to the top pulley, bending and cooling in the air and creating a lever effect that drives the engine. We saw

Has this material science excursion bored you to tears yet? That’s why we love [Bill’s] work. He has always done a fantastic job of demystifying common mysticism and this is no different. The video below does a much better job of illustrating what we’ve described above, but also pull out a Nitinol engine for added wow-factor. A straight piece of Nitinol is bent into a loop around two pulleys. The lower pulley is submerged in hot water, causing the Nitinol to want to straighten out, but it loops back to the top pulley, bending and cooling in the air and creating a lever effect that drives the engine. We saw