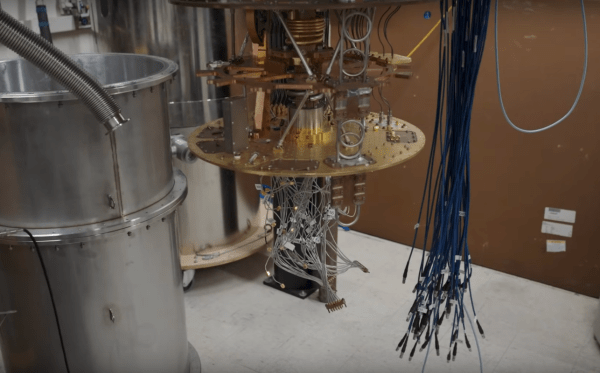

When cleaning out basements, garages, or storage units we often come across things long forgotten. Old clothes, toys, maybe a piece of exercise equipment, or even an old piece of furniture. [Ben] and [Hugh] were in a similar situation cleaning out an unused lab at the University of California Santa Barbara and happened upon an old refrigerator. This wasn’t just a mini fridge left over from a college dorm, though. This is a dilution refrigerator which is capable of cooling things down to near absolute zero, and these scientists are trying to get it to its former working state.

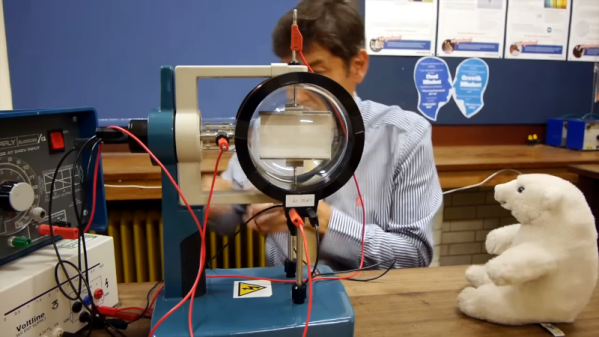

The pair are hoping to restore the equipment to perform dark matter experiments, but the refrigerator hasn’t been in use since about 2016 (and doesn’t have an instruction manual), which is a long time for a piece of specialty scientific equipment to be collecting dust. The first step is to remove wiring and clean it of all the grime it’s accumulated in the last decade. After that, the pair work to reassemble the layers of insulation around the main cooling plate and then hook up a vacuum pump to the device which also needed some repair work.

The critical step at this point is to evacuate the refrigerant lines so they can be filled with expensive Helium-3 and Helium-4. The problem is that there’s still some of this valuable gas in the lines that needs to be recovered, but the risk is that if any air gets into the cold section of the refrigerator it will freeze and clog the whole system. After chasing some other electrical and vacuum gremlins and discovering a manual from a similar refrigerator, they eventually get it up and running and ready for new scientific experiments. While most of us won’t discover a fridge like this cleaning out our attics, this refrigerator powered by rubber bands is a little more accessible to the rest of us.

Continue reading “Rebuilding A $700k Refrigerator” →