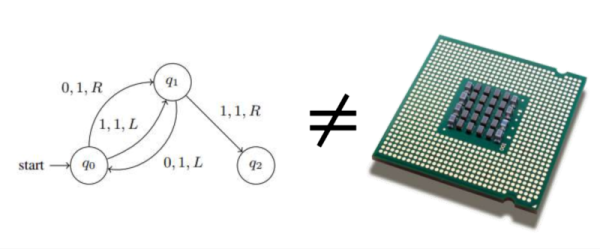

It is funny how exotic computer technology eventually either fails or becomes commonplace. At one time, having more than one user on a computer at once was high tech, for example. Then there are things that didn’t catch on widely like vector display or content-addressable memory. The use of mass storage — especially disk drives — in computers, though has become very widespread. But at one time it was an exotic technique and wasn’t nearly as simple as it is today.

However, I’m surprised that the filesystem as we know it hasn’t changed much over the years. Sure, compared to, say, the 1960s we have a lot better functionality. And we have lots of improvements surrounding speed, encoding, encryption, compression, and so on. But the fundamental nature of how we store and access files in computer programs is stagnant. But it doesn’t have to be. We know of better ways to organize data, but for some reason, most of us don’t use them in our programs. Turns out, though, it is reasonably simple and I’m going to show you how with a toy application that might be the start of a database for the electronic components in my lab.

You could store a database like this in a comma-delimited file or using something like JSON. But I’m going to use a full-featured SQLite database to avoid having a heavy-weight database server and all the pain that entails. Is it going to replace the database behind the airline reservation system? No. But will it work for most of what you are likely to do? You bet. Continue reading “Linux Fu: Databases Are Next-Level File Systems”