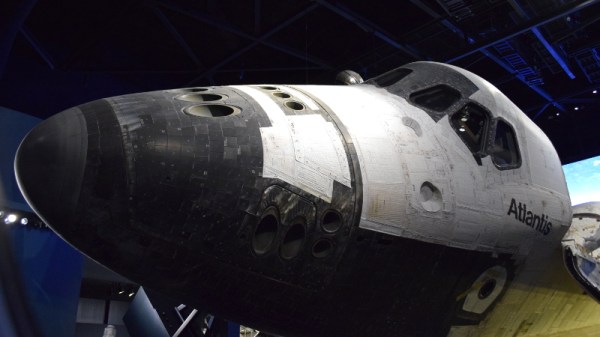

When I got the call asking if I’d be willing to fly down to Kennedy Space Center and cover an event, I agreed immediately. Then about a week later, I remembered to call back and ask what I was supposed to be doing. Not that it mattered, I’d gladly write a few thousand words about the National Crocheting Championships if they started holding them at KSC. I hadn’t been there in years, since before the Space Shuttle program had ended, and I was eager to see the exhibit created for the fourth member of the Shuttle fleet, Atlantis.

So you can imagine my reaction when I learned that the event Hackaday wanted me to cover, the Cornell Cup Finals, would culminate in a private viewing of the Atlantis exhibit after normal park hours. After which, the winners of the competition would be announced during a dinner held under the orbiter itself. It promised to be a memorable evening for the students, a well deserved reward for the incredible work they put in during the competition.

Thinking back on it now, the organizers of the Cornell Cup and the staff at Kennedy Space Center should truly be commended. It was an incredible night, and everyone I spoke to felt humbled by the unique experience. There was a real, palpable, energy about it that you simply can’t manufacture. Of course, nobody sitting under Atlantis that night was more excited than the students. Though I may have come in as a close second.

Thinking back on it now, the organizers of the Cornell Cup and the staff at Kennedy Space Center should truly be commended. It was an incredible night, and everyone I spoke to felt humbled by the unique experience. There was a real, palpable, energy about it that you simply can’t manufacture. Of course, nobody sitting under Atlantis that night was more excited than the students. Though I may have come in as a close second.

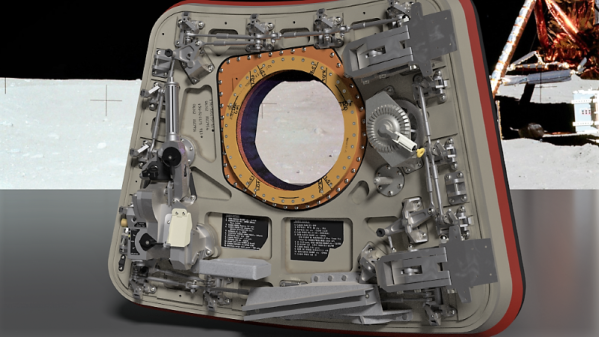

I’ll admit it was somewhat bittersweet to see such an incredible piece of engineering turned into a museum piece; it looked as if Atlantis could blast off for another mission at any moment. But there’s no denying that the exhibit does a fantastic job of celebrating the history and accomplishments of the Space Shuttle program. NASA officially considers the surviving Shuttle orbiters to be on a “Mission of Inspiration”, so rather than being mothballed in a hangar somewhere in the desert, they are out on display where the public can get up close and personal with one of humanities greatest achievements. Judging by the response I saw, the mission is going quite well indeed.

If you have the means to do so, you should absolutely make the trip to Cape Canaveral to see Atlantis and all the other fascinating pieces of space history housed at KSC. There’s absolutely no substitute for seeing the real thing, but if you can’t quite make the trip to Florida, hopefully this account courtesy of your humble scribe will serve to give you a taste of what the exhibit has to offer.

Continue reading “An Evening With Space Shuttle Atlantis” →