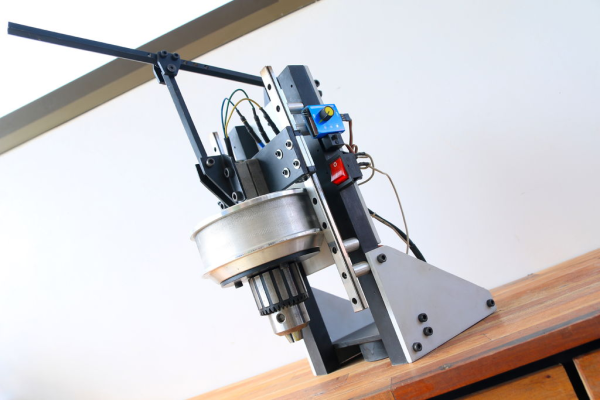

Whether you’re using a soldering iron or a table saw, ventilation in the shop is important. Which is why [Atomic Dairy] built a monster air cleaner called the Fanboy that looks like it should be mounted under the wing of an F-15. Realizing a simple switch on the wall wouldn’t do this potent air mover justice, they decided to build a sound activated controller for it.

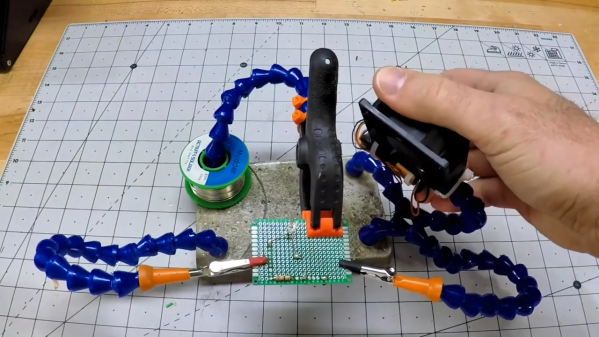

It’s certainly an elegant idea. The sound created once they kick on their woodworking tools would be difficult to miss by even the most rudimentary of sound-detection hardware. At the most basic level, all they needed was a way for an Arduino to throw a relay once the noise level in the room reached a specific threshold.

It’s certainly an elegant idea. The sound created once they kick on their woodworking tools would be difficult to miss by even the most rudimentary of sound-detection hardware. At the most basic level, all they needed was a way for an Arduino to throw a relay once the noise level in the room reached a specific threshold.

Of course it ended up getting a bit more complicated than that, as tends to happen with these kinds of projects. For one, the sound doesn’t directly control the solid state relay used in the fan controller. When the microphone equipped Arduino detects enough noise, it will start a timer that keeps the fan running for two hours. If the tool keeps running, then more time gets added to the clock. This ensures that the air in the room is well circulated even after the cutting and sanding is done.

[Atomic Dairy] also added a few additional features so they could have more direct control over the fan. There’s a button to manually add more time to the clock, and another button to shut it down. There’s even support for a little wireless remote control, so the fan can be operated without having to walk over to the control panel.

We’ve seen some impressive air circulation and dust collection systems over the years, but finding a way to elegantly switch them on and off has always been a problem given the wide array of tools that could be in use at any given time. Sound activation isn’t a perfect solution, but it’s certainly one we’d consider for our own shop.

Continue reading “Building A Sound Activated Shop Fan With Arduino” →