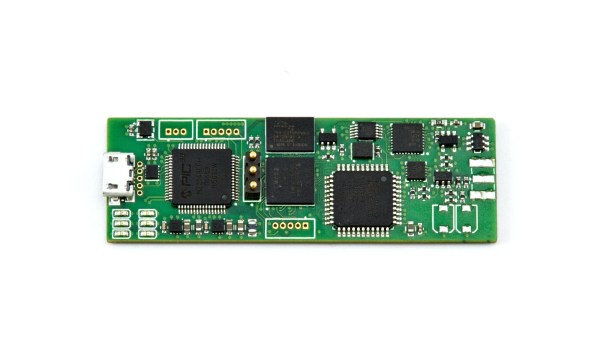

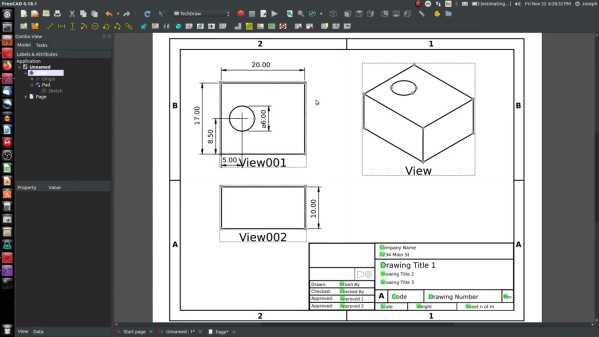

[Mark Omo] sends in his write up on the design of what should hopefully be a sub-$100 oscilloscope in a probe.

Many problems in engineering can be solved simply by throwing money at the them. It’s really when you start to apply constraints that the real innovation happens. The Probe-Scope Team’s vision is of a USB oscilloscope with 60MHz bandwidth and 25Msps. The cool twist is that by adding another probe to a free USB port on your computer you’re essentially adding a channel. By the time you get to four you’re at the same price as a normal oscilloscope but with an arguably more flexible set-up.

The project is also open source. When compared to popular oscilloscopes such as a Rigol it has pretty comparable performance considering how many components each channel on a discount scope usually share due to clever switching circuitry.

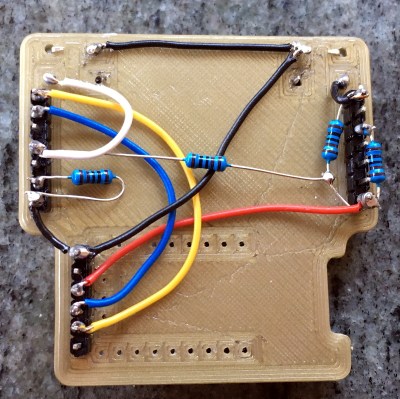

The probe is based around an Analog Devices ADC whose data is handled by a tag team of a Lattice FPGA and a 32bit PIC micro controller. You can see all the code and design files on their github. Their write-up contains a very thorough explanation of the circuitry. We hope they keep the project momentum going!