If you’re like us, the oscilloscope on your bench is nothing special. The lower end of the market is filled with cheap but capable scopes that get the job done, as long as the job doesn’t get too far up the spectrum. That’s where fancier scopes with active probes might be required, and such things are budget-busters for mere mortals.

Then again, something like this open source 2 GHz active probe might be able to change the dynamics a bit. It comes to us from [James Wilson], who began tinkering with the design back in 2022. That’s when he learned about the chip at the center of this build: the BUF802. It’s a wide-bandwidth, high-input-impedance JFET buffer that seemed perfect for the job, and designed a high-impedance, low-capacitance probe covering DC to 2 GHz probe with 10:1 attenuation around it.

[James]’ blog post on the design and build reads like a lesson in high-frequency design. The specifics are a little above our pay grade, but the overall design uses both the BUF802 and an OPA140 precision op-amp. The low-offset op-amp buffers DC and lower frequencies, leaving higher frequencies to the BUF802. A lot of care was put into the four-layer PCB design, as well as ample use of simulation to make sure everything would work. Particularly interesting was the use of openEMS to tweak the width of the output trace to hit the desired 50 ohm impedance.

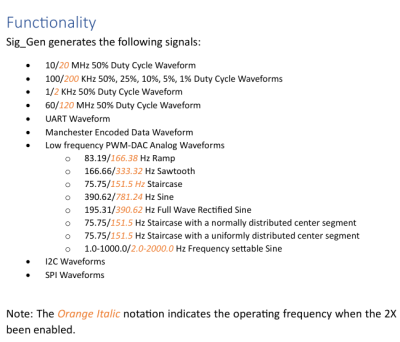

Despite the name it’s not a signal generator as we know it, as it’s not flexible in the signals it generates. Instead, it creates a dozen signals at more or less the same time — from square waves of various frequencies and duty cycles, to a PWM-driven DAC driving eight different waveforms, to Manchester-encoded data I2C/SPI/UART transfers for all your protocol decoder testing.

Despite the name it’s not a signal generator as we know it, as it’s not flexible in the signals it generates. Instead, it creates a dozen signals at more or less the same time — from square waves of various frequencies and duty cycles, to a PWM-driven DAC driving eight different waveforms, to Manchester-encoded data I2C/SPI/UART transfers for all your protocol decoder testing.