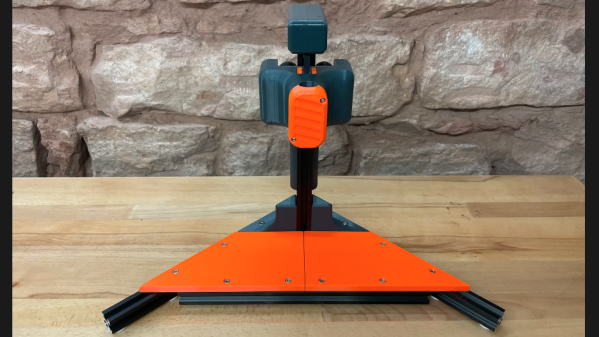

Have you ever considered building your own telescope? Such a project can be daunting, especially if you grind your own mirrors. But with a 3D printer, hardware store bits and bobs, and some inexpensive pre-made mirrors, you too can be the proud owner of your very own own Hadley — a 114/900mm Newtonian Telescope that can cost less than $150 USD to build! Check out the video below the break to get a good scope on the project.

The creator’s stated goal is to “make an attractive alternative to the shoddy, hard to use “hobby-killer” scopes in the $100-200 range“, and we have to say that it appears to have met its goal admirably. The optics — the most complex part of any build — can be easily purchased online, and the rest of the parts are available at your local hardware store.

While the original build was provided in Imperial measures, a metric version is now available. Various contributors have created a rich ecosystem of accessories and alternative versions of various parts, all in the interest of making the telescope more useful. Things like tripod mounts, phone mounts (for use with your favorite star chart app) and more are only a click away. The only real question to answer is “What color filament will I use?”

Of course, sometimes light waves can get a bit long in the tooth, and for those cases you’ll want a radio telescope, which can also be DIY’d thanks to the availability of satellite dishes and SDR dongles!

Continue reading “3D Printed Newtonian Telescope Has Stunning Looks, Hadley Breaks The Bank”