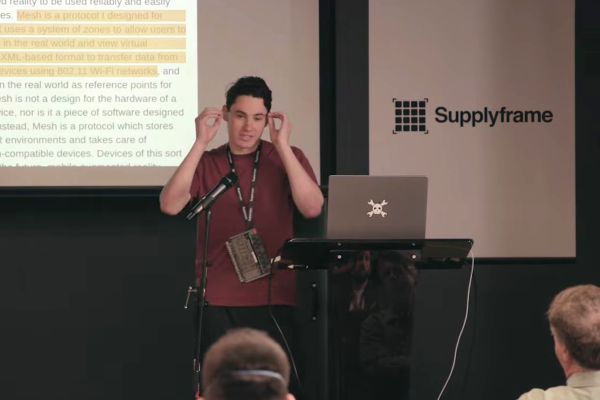

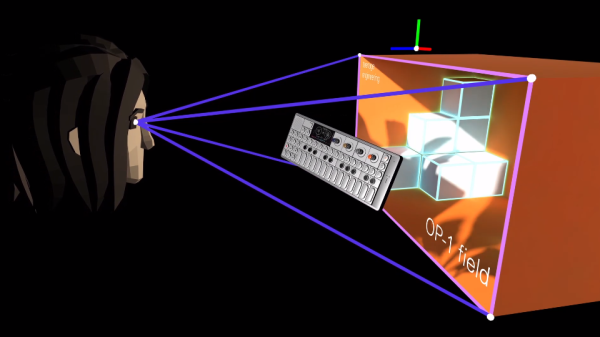

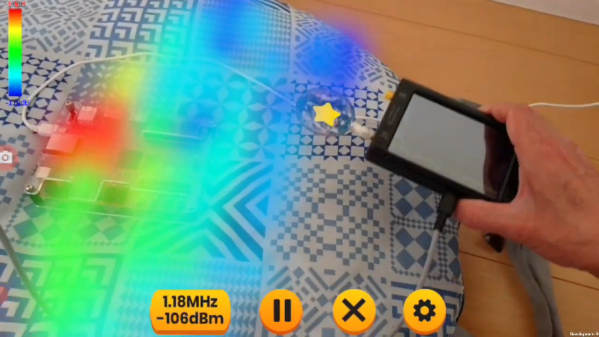

There’s something very tantalizing about an augmented reality (AR) overlay that can provide information in daily life without having to glance at a smartphone display, even if it’s just for that sci-fi vibe. Creating a system that is both practical and useful is however far from easy, which is where Aedan Cullen‘s attempt at creating what he terms a ‘practical augmented reality device’.

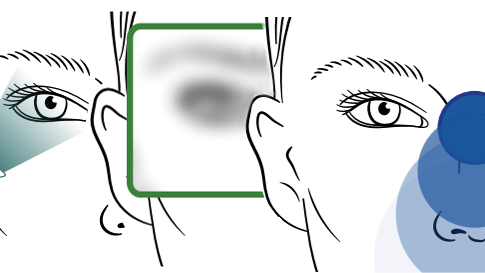

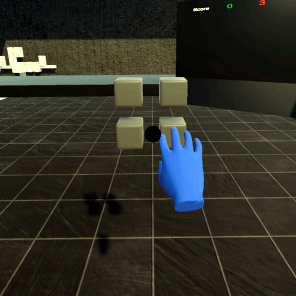

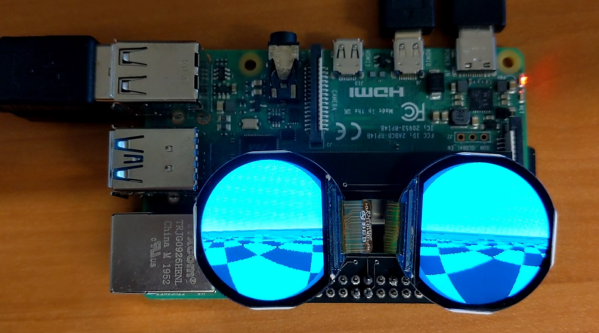

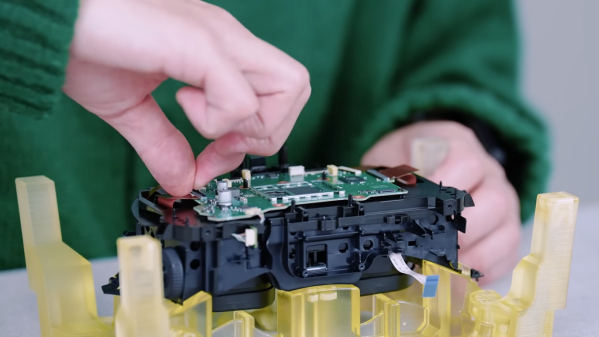

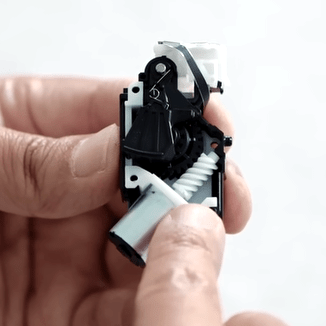

In terms of requirements, this device would need to have a visual resolution comparable to that of a smartphone (50 pixels/degree) and with a comparable field of view (20 degrees diagonal). User input would need to be as versatile as a touchscreen, but ‘faster’, along with a battery life of at least 8 hours, and all of this in a package weighing less than 50 grams.

Continue reading “Supercon 2022: Aedan Cullen Is Creating An AR System To Beat The Big Boys”